En: The Anti-Masonic Movement

Inhaltsverzeichnis

The Anti-Masonic Movement

Source: Phoenixmasonry http://pictoumasons.org/library/Gibbs,%20E%20B%20~%20The%20Anti-Masonic%20Movement.pdf

Original-Source: The Builder MagazineDecember 1918 - Volume IV - Number 12

BY BRO. EMERY B. GIBBS, P. D. G. M., MASSACHUSETTS

THE institution of Masonry was introduced into the Colonies at an early stage of their existence. The growth was slow at first, but after the Revolution it spread more rapidly. From 1790 to 1820 the growth was very marked. It had the sanction of many of the most distinguished men of the country. Nothing had occurred up to 1826 to mar its progress. Men prominent in Masonry spoke publicly of the many positions of trust and importance held by men belonging to the Masonic Fraternity. Some were indiscreet enough to announce that Masonry was exercising its influence in the pulpit, in the legislatures, and in the courts. To this but little attention was paid until the Morgan episode in 1826.

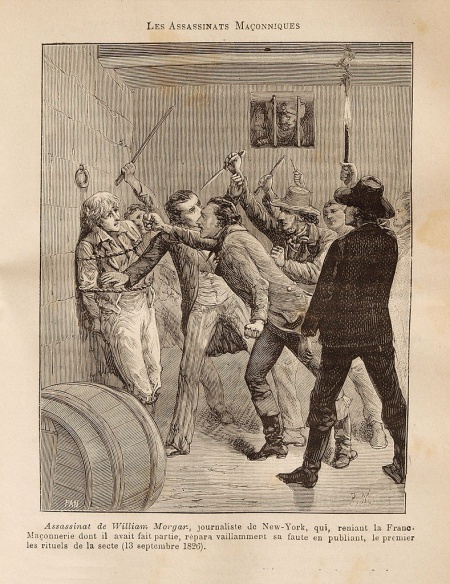

William Morgan was a native of Virginia, born in Culpepper county in 1775 or 1776. Little is known of his early history. Among the assertions regarding it is one story that he was a Captain in General Jackson's army at the battle of New Orleans, and another that he belonged to a band of pirates and was sentenced to be hanged, but pardoned on condition that he enter the army. But little credit should be given to either of these reports.

In October, 1819, at the age of forty-three or forty four, he married Lucinda Pendleton of Richmond, Virginia, then in her sixteenth year. In 1821 Morgan and his wife moved to Canada, where he undertook the business of a brewer near York in the Upper Province. The loss of his brewery by fire reduced him to poverty and he then moved to Rochester, New York, where he worked and occasionally received assistance from the Masonic Fraternity. From Rochester he went to Batavia, in the county of Genesee, and worked at his trade, which was that of a mason, until his disappearance in 1826.

During his residence at Batavia he was intemperate, frequently neglecting his family. With but little education, it is said he had a fair knowledge of writing and arithmetic, kept reasonably good accounts, was a man of common sense, pleasing manner, and when not under the influence of strong drink was a pleasant, social companion among his fellows.

No one has been able to ascertain where he was made a Mason. He met with the lodge at Batavia. In 1825 or 1826 a petition to the Grand Chapter of the state was drawn up to obtain a charter for a chapter of Royal Arch Masons in Batavia. This petition Morgan signed. Before it was presented to the Grand Chapter, others who had signed it and knew his habits and character were unwilling to have him become a member. A new petition was prepared and signed and presented without Morgan's name. On this petition a charter was obtained. When Morgan learned that he was not a charter member and knew that he could be admitted only by a unanimous vote, he was surprised and offended at being excluded from the Chapter, and from that time became an active and very ardent foe of Masonry.

A few years previously one David C. Miller had established himself in Batavia and was publishing a local newspaper. Miller's undertaking as an editor and printer was unprofitable. He was a man of cunning and of a certain ability; reputation not very good, and of objectionable habits. At some time prior to his living in Batavia, he had been initiated as an Entered Apprentice at Albany, New York. Objection being made to his further advancement on the ground of his character, he never received the second and third degrees.

Morgan and Miller, having a common grievance against the Masonic Fraternity, planned together how they might create something of a sensation and acquire a substantial, if not great fortune, out of the venture to disclose the secrets of Freemasonry. Their threats and suggestions were regarded at first as of no significance. The Masons at Batavia paid little attention to the rumors until it was evident that Morgan and Miller were bound to carry out their threats and publish in Miller's paper a complete revelation of so-called Masonic secrets. There was a strong feeling on the part of a few who were quite as much opposed to Morgan and Miller personally as they were zealous in the cause of Masonry that this publication should be prevented. Soon the matter became the topic of street conversation and one night an effort was made to sack Miller's office and some forty or fifty persons assembled for the purpose of breaking in and securing the manuscript. Nothing was accomplished at this time, but two nights later an attempt was made to set fire to the office. Whether this attempt to burn the place was made by persons who were opposed to Morgan and Miller, or made by Miller himself, was an open question and never satisfactorily settled. Masons offered a reward of one hundred dollars for the discovery of the incendiary. A man by the name of Howard, suspected as an accomplice, fled, no one knows where, after a warrant had been issued against him.

The details of Morgan's arrest for petty larceny, his acquittal, his arrest again for debt, and his discharge after the debt had been paid, his ride in a carriage to Rochester with several other men, and from there to Fort Niagara, are all familiar. One writer on this event, himself not a Mason, traces Morgan to Fort Niagara and concludes by saying that there is no reliable evidence of what happened to or became of Morgan after he was taken to Fort Niagara.

To the question, what became of Morgan? no definite answer has been, and so far as we can learn, ever can be given.

The American Quarterly Review for March, 1830, published an article on the Anti-Masonic excitement, by Henry Brown, an attorney-at-law of Batavia, New York. This article was reviewed and commented on by Masons and by those who were not Masons, as being a carefully prepared and well-presented statement of what occurred.

Brown, in narrating the events which followed the disappearance of Morgan and the efforts made to discover his body, particularly the searching of the Niagara River and a part of Lake Ontario, all without success, and when a good deal of the public excitement in that locality had abated, states that a body was discovered on the 7th of October, 1827, in the town of Carlton about forty miles from Fort Niagara. It was lying at the water's edge. An inquest was held, witnesses who were personally acquainted with Morgan were examined, and the jury pronounced it the body of some person to them unknown who had perished by drowning. The body was in a decomposed and offensive state at the time, and was quietly buried.

This inquest was published in the newspapers and suspicion was at once excited that this was the body of Morgan. Several men from Batavia and Rochester had the body disinterred, and then discovered, or pretended that they discovered, points of resemblance between this body and Morgan. They had the body watched over night to prevent the Masons from carrying it away. Mrs. Morgan was visited and went to Carleton and inspected the body.

"On arriving at Carleton on the 15th of October the body was slightly and imperfectly examined. It was bloated and entirely black, putrid on its surface and offensive (beyond anything conceivable) to sight or smell. Its dress did not correspond with anything which they had seen before, and the religious tracts in the pocket staggered some of the most credulous. There was not in fact a single circumstance in the dress, size, shape, color or appearance of the body which pointed it out as Morgan."

The men active in fomenting the excitement were unwilling to lose the advantage of so valuable an asset. A second inquest was held over this body which, if it had been that of Morgan, must have been thirteen months in the water.

Mrs. Morgan testified she believed it to be the body of her husband, though the clothes were entirely different from those he wore at the time of his disappearance, and there were found in the pocket a number of religious tracts of a description not known in the neighborhood of Batavia.

One witness recognized the shape of his head; another the outline of his features; a third the color of his hair; a fourth of the whiskers; a fifth the teeth, and a sixth the hair inside of the ears. On these grounds the jury decided that this was the body of William Morgan and that he came to his death by drowning.

The body was removed with great parade of solemnity to Batavia and there interred in the presence of a vast crowd, and a funeral oration pronounced by one Cochran, who, Brown says,

"Sometimes when sober and sometimes when otherwise, preached in the vicinity and was then assistant editor to Col. Miller."

(Miller was associated with Morgan in the publication of the so-called Masonic secrets.)

These events inflamed the indignation of the people to the highest pitch and Freemasonry was detested more bitterly than ever. It was on the eve of an election.

"The cry of vengeance was wafted on every breeze and mingled with every echo of the lake where Morgan's ghost, it was said, performed its nightly rounds."

About this time a notice appeared in the Canadian newspapers that one Timothy Monro, of Clark, in the District of New Castle in Upper Canada, left that place for Newark in September, 1827, in a small boat, and was drowned in the Niagara river while attempting to return. A description of the body found in Carleton, together with the clothing and religious tracts found in the pocket, being published in the newspaper soon after the first inquest and coming to the knowledge of Monro's friends, induced the belief that the body found in Carleton was his. Mrs. Sarah Monro, widow, accompanied by her son and one John Cron, her friend, after hearing of this body, went at once to examine it. In consequence of their testimony, the body was a second time disinterred and a jury of inquest a third time summoned.

After hearing all the evidence, this jury decided that it was the body of Timothy Monro, who was drowned in Lake Ontario, September 26, 1827. Mr. Brown in his article gives the testimony of the witnesses at length, which is entirely conclusive as to the propriety of this last verdict, in which it was proved that the body pronounced to be that of Morgan was at least five feet nine inches long, whereas the height of Morgan when alive was less than five feet six inches. It also appeared in evidence that the hair of his body had been so disposed by art as to make it appear like that of Morgan.

The Morgan excitement was rapidly waning and the political situation of the Anti-Masonic party was becoming sadly in need of some new stimulant, when it was furnished by the confession of one Hill, who declared himself one of the murderers of William Morgan. He was arrested and committed to jail in Buffalo, where he signed a confession. He was then removed to Lockport for trial, but refused to go before the Grand Jury to testify to the truth of his confession. The Grand Jury, believing him insane, refused to find a bill and he was discharged. No clew to his conduct has ever been discovered. It may be an injustice to the politicians to suggest that this man, carefully coached, played his part, knowing that no serious harm would come to him, and so contributed to the excitement and bitterness of feeling against the Masons. In any event, his part was well played and the effect far-reaching.

More than forty trials took place of persons suspected of being concerned in Morgan's disappearance. The greater number resulted in acquittals. Several, however, were convicted and served substantial sentences.

M.W. Brother Gallagher stated in an address that Maj. Benjamin Perley Poore, for many years Washington correspondent of the Boston Journal, while in Smyrna, Turkey, in 1839, knew that Morgan was then alive and identified by men who had known him in New York.

I have referred to these different reports as to what became of Morgan, but I leave it as I began, with uncertainty and inability to determine his fate.

Prior to the Morgan incident there may have been some excuse for accusing Masons of political activity and using the organizations for political purposes.

In 1816, John Brooks, a Mason, and Samuel Dexter, not a Mason, were opposing candidates for the office of Governor of Massachusetts. In 1798, Mr. Dexter had written a letter to Grand Master Bartlett strongly condemning and ridiculing Freemasonry.

In 1816, Benjamin Russell was editor of the "Poston Centinel" and also Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Massachusetts and an ardent supporter of General Brooks as against Mr. Dexter. In the "Boston Centinel" of March 30, 1816, appeared the following paragraph:

TO THE MASONIC FRATERNITY

Brethren:--It need not be repeated that the internal regulations of your benevolent order exclude all discussions of political dogmas. But every Master Mason knows that his public obligation obligates him to discharge the duties he owes to the state with diligence and fidelity.

When two candidates, therefore, present themselves for his suffrage, he is not bound to inquire to what party the one or the other belongs; but whether he is "a good man and true," and faithful to the Constitution which he may be called upon to administer. And all other things being favorable, he is bound by every Masonic obligation to give his vote for the one who is a Free and Accepted Brother in preference to one who is not.

Brother John Brooks shall receive the vote of A MASTER MASON."

Square and Compass

In New York, in the year 1824, De Witt Clinton was candidate for Governor against a candidate who was not a Mason. At that time Mr. Clinton was Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of New York, General Grand High Priest of the General Grand Royal Arch Chapter of the United States, Grand Master of the Grand Encampment of Knights Templar for the United States, Sovereign Grand Commander of the Grand Consistory of the United States. He also held other Masonic offices. All these Masonic titles, from the highest to the lowest grade, were centered in Mr. Clinton at about the same time. A paper called the "National Union" was published in New York solely to aid his election as Governor. Samuel H. Jenks, of Nantucket was the editor. Mr. Jenks was the Deputy Grand Master in Massachusetts in 1825. The following was published in that paper October 30, 1824:

"Brethren:--Your former Grand Master is now a candidate for the support of the 'free and accepted.' De Witt Clinton, if there be any virtue in the cardinal principles of your faith, will receive your undivided suffrage for Governor. It is in periods of trial, like the present, that the wisdom of Freemasonry has been exercised, its strength tested, and its beauty displayed. Amidst the dark ages of past time, the great lights of our Order, though often obscured, have never been extinguished. Shall they now be eclipsed by the 'introduction of strangers among the workmen?' Will you suffer the political edifice to be 'daubed with untempered mortar?' No, surely! The architect of your internal prosperity is before you. Enter warmly into the cause of your Brother--pass onward to the ballot boxes, with the tokens of your zeal and fidelity--and by your united votes contribute to raise the State to that exalted rank to which she is so justly entitled.

(Signed) THE WIDOW'S SON."

Mr. Clinton's election was accomplished by a very great majority. This was in 1824. Mr. Clinton was Governor of New York in 1826, when Morgan disappeared.

The political situation then suddenly changed. In the spring of 1827 Masons were proscribed simply because they were Masons in Genesee and Monroe countries. In the Fall of 1827 the Anti-Masonic party announced its object as the destruction of Freemasonry through the instrumentality of the ballot box.

George A. S. Crooker was nominated for Senator the eighth district. Although he was defeated, the Anti-Masonic party carried Genesee, Monroe, Livingston and Niagara counties in the face of both the Democratic, or Jacksonian party, and the National Republican or Adams party.

In 1828 Solomon Southwick of Albany, was nominated for Governor of New York. His total vote was 33,345, and, while defeated, in the more radical counties he received a very large vote.

In the State election of 1829 the eighth district elected Albert H. Tracy senator by a majority of 8000 votes, and the same year they carried fifteen counties, with a total vote in the state of over 67,000.

In 1830, Francis Granger was nominated for Governor at a convention held at Utica in which forty eight counties were represented by one hundred and four delegates. He received a vote of 120,361, but was defeated.

Granger was nominated again in 1832 and again defeated, although his vote was 156,672.

To show the rapid growth of the Anti-Masonic party in New York, the following votes are given:

1828 33,345 1829 68,613 1830 106,081 1831 98,847 1832 156,672

In 1833 the estimated strength of the Anti-Masonic party in the United States was 340,800. Its most rapid growth was in the State of New York.

In Maine the Anti-Masonic vote in 1831 was 869; 832, 2384; in 1833, 1670. That was the end of the party in Maine.

In Vermont the feeling was so intense that in 1832 she cast her vote in favor of the Anti-Masonic candidate for President, and had the distinction of being the only state in the Union to be carried by the Anti-Masonic party.

In Pennsylvania the feeling was so intense that at a convention of Anti-Masonic delegates held in Philadelphia, September 11, 1830, the report of a committee was adopted which recited that "Morgan was foully murdered," rehearsed the several obligations of Freemasonry, and demanded the suppression of the institution. Among the reasons given for this drastic action may be cited the following:

- "To this government Freemasonry is wholly opposed. It requires unresisting submission to its own authority, in contempt of public opinion, the claims of conscience, and the rights of private judgment."

- "The means of overthrowing Freemasonry cannot be found in any, or in all, of our executive authorities. They cannot be found in our judicial establishments."

- "The only adequate corrective of Freemasonry--that prolific source of the worst abuses--is to he found in the right of election, and to this we must resort."

- "~Freemasonry ought to be abolished. It should certainly be so abolished as to prevent its restoration. No means of doing this can be conceived so competent as those furnished by the ballot boxes."

In 1836 the Anti-Masonic party held its last national convention at Philadelphia and its influence as a factor in politics practically ended at this time.

In reading accounts of the campaign carried on during these Anti-Masonic days, one is impressed with the bitterness, fierceness and intensity of the Anti-Masonic spirit. One writer describes it in the following language:

- "That fearful excitement which spread over our land like a moral pestilence, which confounded the innocent with the guilty, which entered even the temple of God, which distracted and divided churches, which scattered the closest ties of social life, which set father against son and son against father, arraigned the wife against her own husband, and in short wherever its baleful influences were most felt, deprived men of all those comforts and enjoyments which render life to us a blessing."

Resolutions were adopted in the different legislatures calling for investigations, demanding the surrender of the charters of the Grand Lodges, and looking towards every possible way of terminating the Masonic institution.

In Rhode Island a committee of five was appointed by the legislature, no one of them Masons. This committee held eighteen sessions in the principal cities of Rhode Island, hearing all the evidence offered, whether hearsay evidence or evidence in the proper form as admitted in courts, and then made a very complete report in which it declared that all the charges presented to it against the Masonic order were baseless and slanderous.

In Massachusetts our Grand Lodge surrendered its act of incorporation to the legislature and turned its property over to trustees to be held by them, rather than engage in any controversy on the subject with the legislature. It is interesting, however, to know that a committee of the legislature appointed in 1834, after long investigation and hearings, made an elaborate report, from which the following is taken:

AN INVESTIGATION INTO FREEMASONRY BY A JOINT COMMITTEE OF THE LEGISLATURE OF MASSACHUSETTS, MARCH, 1824.

The Joint Committee of the Central Court to whom were referred the memorials of Otis Allyn and other citizens of the Commonwealth, praying for a full investigation into the nature, language, ceremonies, and form of rehearsing extra-judicial oaths in Masonic bodies, and, if found to be such as the Memorialists described them, that law may be passed, prohibiting the future administration of Masonic, and such other extra-judicial oaths as tend to weaken the sanction of civil oaths in Courts of Justice; and praying also for a repeal of the charter granted by this Commonwealth to the Grand Lodge of Massachusetts, have attended the duty assigned them, and ask leave to

REPORT

The committee are fully impressed with the sacred character of the right which the people of this Commonwealth, in their Bill of Rights, have retained to themselves, of petitioning their Legislature for the redress of grievances. The right has been exercised in the present instance by more than eight thousand citizens, in one hundred and twenty Memorials referred to the Committee, complaining of the institution of Freemasonry as a grievance.

The report then goes on to recite different reasons and motives for these Memorials and the method of conducting their investigations; that they had invited the officers of the Grand Lodge of Massachusetts and all other Masons to attend; that neither the Grand Master nor any other member of the Grand Lodge, nor any adhering Mason appeared before them, and that the committee had failed in its efforts to have anyone appear before it who should fairly represent the Masonic Fraternity; that at the request of counsel for the petitioners invitations were sent to the following adhering Masons:

Rev. Paul Dean, Rev. Samuel Barrett, Rev. Asa Eaton, Rev. Sebastian Streeter, Rev. William Cogswell, Benjamin Russell, Esq., Robert G. Shaw, Esq., Samuel Howe, Esq., Hon. Charles Jackson, Hon. Josiah J. Fiske.

Two of these respectfully declined attendance in writing; the others neither replied nor attended. At the request of the committee, the House gave them power to send for persons and papers, but the Senate refused to concur in the action of the House.

Upon such information as the committee could obtain from the petitioners, among whom were many seceding Masons, they submitted the following conclusions:

- "First. That Freemasonry is a moral evil; inasmuch as it holds its proceedings shrouded by cautious and almost impenetrable secrecy, and at an hour of darkness, which withdraws its members unseasonably, from that family circle, which ought to be the first care and the first solace of every good citizen; as it offers temptations in the form of 'refreshments,' to a departure from that sobriety and temperance, which should mark the character of an intelligent and moral community; as it familiarizes the mind, theoretically at least, to the contemplation of scenes of violence and blood; and especially as some of its rites and ceremonies are offensively sacrilegious, profaning what the community generally religiously respect; thus undermining those sentiments of piety, which are acknowledged to be the very basis and safeguard of morality.

- "Second. That Freemasonry is a pecuniary evil; inasmuch as it collects from the community, under the false pretenses of extensive charity and peculiar science, large amounts of money, which are afterwards chiefly expended in unprofitable entertainments, parades, and trinkets, which, in the language of an eminent departed statesman, 'a well-informed savage would blush to wear.'

- "Third. That Freemasonry is a political evil; inasmuch as it is a government claiming existence independent of civil governments, and administering oaths, which, from their number and frequency, tend to impair the binding force of civil oaths-- threaten penalties, severe even to barbarity, and calculating to have an appalling and controlling effect on weak and uninformed minds--and in their tenor conflict with the civil obligations of the citizen, calling on him either to violate the latter in obedience to his Masonic oaths, or to violate his Masonic oaths in obedience to his civil obligations."

The report continues to set forth the reason for its conclusion and the following is taken from part of the report relating to the second finding:

- "The By-Laws of the Grand Lodge appropriate one fourth part of the annual fees and one-third part of all initiation fees paid by subordinate lodges, to the charity fund; that is, two dollars for every lodge, and one dollar for every initiation in the State. Thus one hundred one lodges would pay $808, and if nine hundred Masons were made annually, as was the increase in 1826, they would pay $2700 more, of which $1206 would go to support the 'dignity' of the Grand Lodge, and $502 be added to the charity fund, the interest alone of which can be applied to charity--so that by this process, it would require $2700 to enable this Charitable Society, the Grand Lodge, to distribute in charity $30.12 a year!"

Lodge dues $8. Initiate dues to Grand Lodge $3.

(1/4 of $808 equals $202. 900 initiates would pay $2700. 1-3 of $2700 equals $900. $202 plus $900 equals $1102 instead of $502.

$1102 at 6 per cent interest would produce $66.12 instead of $30.12 as so solemnly declared by this legislative committee of Anti-Masons.)

The period 1820 to 1840 was one of intense religious activity.

On July 4, 1827, in the Seventh Presbyterian Church of the city of Philadelphia, Ezra Stiles Ely said in a sermon:

"I propose, fellow-citizens, a new sort of Union or if you please a Christian party in politics, which I am exceedingly desirous all good men in our country should join, not by subscribing to a constitution, but by adopting and avowing to act on religious principles in all civil matters."

At this time also the more orthodox members of the Congregational church were alarmed at the different beliefs creeping into their fold. For this purpose it was proposed by many to adopt synods like those of the Presbyterian church in order to define their tenets exactly. A large body of the church even desired the union of the Congregational and Presbyterian churches.

The Anti-Masonic party having so many religious men in its ranks, and being at this time in a crusade in which the churches were distracted, naturally entered as another element in the religious distress of the period. In New England this was especially true, as the party there was composed of the older religious country people, already in opposition to the liberal spirit of the cities.

The Anti-Masonic party received the name of the "Christian Party in Politics."

Every effort was directed against Masonic preachers and laymen. Churches in their councils condemned the order. Before the disappearance of Morgan, the Presbyterian church at Pittsburgh in January, 1821, condemned the institution as "unfit for professed Christians." After the Morgan incident the Presbyterians required their ministers to renounce Masonry and their laymen to sever all connections with it and hold no fellowship with Masons. The Congregationalists took practically the same attitude in New England and Eastern New York. They attacked at one and the same time the Unitarians, the Universalists, and the Masons. In New England Anti-Masonry was looked upon as "nothing more than Orthodoxy in disguise."

In one of the Vermont papers opposed to the AntiMasons appeared a letter in which the writer made the following appeal:

"Universalists, awake from thy slumbers, and show to these Orthodox (Anti-Masons) that we are yet a majority and that we calculate to retain the majority." March 11, 1834.

As early as 1823 the General Methodist Conference prohibited its clergy from joining the Masons. In Pennsylvania during the Masonic excitement it was said by the Anti-Masons that "No religious sect throughout the United States has done more for the Anti-Masonic powers than the Methodists." It forbade its members to join lodges or be present at any of their processions or festivals and passed strict rules against ordaining any ministers who belonged to the Order. The Methodist church was rent and torn by the struggle, and many churches, fearing strife, did not allow the question to come up, but passed non-partisan resolutions.

The Baptist church also was rent with dissensions over the question, although not to so great an extent as the Presbyterians, Congregationalists, and Methodists. At a convention of delegates from Baptist churches held at LeRoy, New York, January 30, 1827, it was

"Resolved, that all such members as belong to the Baptist church and who also belong to the society of Freemasons, be requested to renounce publicly all communications with that order, and if the request is not complied with in a reasonable time, to excommunicate all those who neglect or refuse to do so."

Many of the friends of temperance, which was a growing reform at this time, were also enemies of Masons.

Another peculiarity of Anti-Masonry is that it found its chief support in the country and not in city. It is interesting to note that Anti-Masonry was essentially a New England movement. There were exceptions, but in New England and New York and throughout the path of New England emigration the party was strongest. Most of the leaders in New York, like Weed, Granger, Holley, Ward and Maynard, were of New England extraction. The party in Pennsylvania was led by men of New England extraction and was called by the Democrats "a Yankee concern from beginning to end."

The Anti-Masons accused the newspapers of being "muzzled" by the Masons. Anti-Masonic papers were established. In 1832 there were one hundred and forty one of these papers. New York had forty-five weeklies and one daily, while Pennsylvania had fifty-five weekly papers.

Considering all these conditions, the Morgan incident was but the spark that lighted the fire. The fire was fanned and controlled by some of the shrewdest political leaders this country has ever seen. The greatest of all of these politicians were Thurlow Weed of New York and Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania, while in New England, Hallett of Rhode Island was active, and Phelps and Thatcher of Massachusetts may be mentioned among the most prominent, although there were many very active in New England.

In 1826 there was a general practice, which had prevailed for years, of giving credit for the degrees. The door of Masonry was thrown open to a great many. It was, as we say, popular to belong to the Masonic Fraternity. It is possible that during the period immediately preceding the Morgan episode a good many had been accepted into the Fraternity without being carefully investigated, or if they were, the committees and lodges were too eager and anxious to swell their numbers to exercise that careful scrutiny of the applicant which has been found so essential if the lodges are to maintain that high standard of character which the institution warrants; consequently, when the storm burst and the Fraternity was openly charged with violating the law of the land and the murder of an innocent citizen, a good many of those who dropped out or became seceding Masons improved the opportunity to destroy their financial indebtedness and at the same time gain some notoriety in their several communities.

The work of the lodges fell off very rapidly. In some states the Grand Lodges suspended their meetings for years. The Grand Lodge of Vermont had but seven lodges represented at its meeting in 1834. In 1836 the Grand Master, the Grand Secretary, and the Grand Treasurer of Vermont were empowered to meet every two years and adjourn the Grand Lodge biennially or oftener. This was done during the years 1837, 1838, 1840, 1842 and 1844, but in 1845 these Grand Officers took counsel to resume labor. It also appears from their records that various constituent lodges at that time resumed labor. This would indicate that their communications had never legally ceased and their charters had not been surrendered. Probably these lodges followed the civil law as to associations and so maintained a consecutive legal existence from a date prior to the Anti-Masonic period.

In Maine the Grand Lodge failed to meet for several years and, had a nominal meeting in other years. While from 1834 to 1843 the Grand Lodge met annually, at one meeting they were without a representative from a single lodge, and but twice during this period of nine years did they have representatives from more than four lodges. Nearly all the lodges in Maine during this period or some part of it, suspended their meetings and became dormant, even if they did not surrender their charters.

In New Jersey the Grand Lodge in 1824 and 1825 had representatives from twenty-two to thirty-three lodges. After this period of opposition the lodges in New Jersey were reduced to six.

In New York there were four hundred and eighty lodges in 1826 with a membership of about twenty thousand. From 1827 to 1839 the Grand Lodge maintained its annual meetings, but only fifty to ninety different lodges were represented in that time. In 1835 there were but seventy-five lodges in the State of New York; twenty-five of these were in the city of New York, with a membership of about three thousand. In 1839 there were seventy-five lodges in the state, twenty-two were in New York City and Brooklyn and fifty-three in the remainder of the state. Masonry was at its lowest ebb in New York about 1840.

There are many remarkable instances of loyalty and heroism in connection with these local lodges. One or two instances will suffice. Olive Branch Lodge No. 39, at Le Roy, in Genesee County, did not suspend its communications, and was recorded as the "Preserver of Masonry" in Western New York; seven of its most zealous and devoted members entered into this solemn agreement:

- "To meet once in four weeks for the purpose of opening and closing the lodge and keeping up the work."

This agreement was literally kept, and never once during that time, although obliged to travel a distance of more than thirty miles, did they fail to have their meetings.

Union Lodge No. 45, at Lima, Monroe county, continued to hold its regular meetings, although it was fiercely assailed again and again.

Batavia lodge, where the Morgan trouble began, lay dormant for sixteen years, but was revived in 1842.

On June 17, 1825, occurred the laying of the cornerstone of Bunker Hill Monument, by the officers of the Grand Lodge of Massachusetts, who were honored by the presence of Brother LaFayette, friend and companion of George Washington.

Eighteen hundred and twenty-five was the last prosperous year Massachusetts Masonry was to see fol two decades. That year the number of lodges rose to one hundred and seven. In 1844 it had sunk to fifty two and at one Communication of the Grand Lodge only eight lodges were represented.

In 1833, the meeting of December 12th was adjourned to December 20th, and at that meeting the only business transacted, according to the records, was the passing of the following vote:

- "Voted: That R. W. Francis J. Oliver, R. W. Augustus Peabody, R. W. Joseph Baker, R. W. John Soley, and R. W. Charles W. Moore, be a committee to consider the expediency of surrendering the act of incorporation of the Grand Lodge, and report at the next meeting."

The next meeting was held December 27, 1833, and the following action was taken:

- "Voted: That the Master and Wardens of this Grand Lodge be authorized and directed to surrender to the Legislature the act of incorporation granted to the Master, Wardens and Members of the Grand Lodge of Massachusetts, June 16, 1817, and to present therewith the foregoing memorial signed by them."

The memorial referred to is a dignified, carefully prepared statement of the reasons for surrendering this act of incorporation and a plain statement of their position on all questions involving the principles of Masonry.

At this meeting it was reported that the sale of the Masonic Temple as authorized, had been made to Robert Shaw.

In 1843, December 27, the Grand Lodge met and held a Lodge of Instruction, at which the three degrees were fully worked and exemplified by the Grand Lecturers with "facility and skillfulness." More brethren from the country were in attendance at this meeting than any previous occasion for ten years. In the same year a new and revised edition of the Grand Constitutions was adopted.

In 1845, December 27, two years later, a Grand Lodge of Instruction was called at 9 a.m., at which the representatives of twenty-seven lodges were present. The work of the three degrees was exemplified by the Grand Lecturers and favorable comments on their efforts are recorded.

On June 17, 1843, occurred the great celebration of the completion of the Bunker Hill Monument, at which were present the chief magistrates and dignitaries of the nation and some of the states. In the Proceedings of the Grand Lodge occurs this comment:

- "Those who had the direction of the great jubilee did not feel the propriety of inviting our Grand Lodge to assist in the ceremonies."

King Solomon's Lodge, of Charlestown, was especially invited, and it seems that the members of the Grand Lodge joined with the members of King Solomon's Lodge in the procession and so participated in the proceedings, but with great regret that they were not permitted to participate officially in the proceedings, in view of the illustrious Masons who participated in the battle that this monument was to commemorate.

Twenty years after the Morgan episode, the editor of "Letters on Freemasonry" by John Quincy Adams, stated in an introduction to those letters as published in 1847:

- "The excitement which arose in consequence of the disclosures then made had the effect, at least for a time, if not permanently, to check the further spread of that association. The legislative power of some of the states was invoked, and at last actually interposed, to prevent the administration of extra-judicial oaths, including of course all such as were constantly taken in the Masonic Order. This was the furthest point which the opposition ever reached. It did not succeed in procuring the dissolution of the organization of the order, or even the repeal of the charters under which it had recognized existence in the social system. From the moment of the adoption of a penal law deemed strong enough to meet the most serious of the evils complained of, the apprehension of further danger from Masonry began to subside. At this day (1847), the subject has ceased to be talked of. The attention of men has been gradually diverted to other things, until at last it may be said that few persons are aware of the fact, provided it be not especially forced upon their notice, that not only Freemasonry continues to exist, but also that other associations partaking of its secret nature, if not of its unjustifiable obligations, not merely live, but greatly flourish in the midst of them."

A careful reading of many articles published and resolutions passed at about the time of the Morgan episode indicates that a few members of the lodge at Batavia thought they were serving a good purpose by securing Morgan's manuscript before it was published and separating Morgan from Miller, editor of the local paper. Quite a number of Masons were knowing to the plans.

These plans included an agreement with Morgan that he should destroy all the manuscript and printed sheets connected with his proposed publication; he was to quit drinking, and from the money to be paid clothe himself decently and provide for the immediate wants of his family; refuse all further interviews with his partners; promise that he would not disclose this arrangement to anyone, and that within a short time he would go to a remote locality in Canada, where he was to settle down, his family to be supplied with money and transportation to join him, and a substantial sum paid to Morgan for giving up the publication and the expected income from these disclosures. Morgan was to be well treated and his family provided for until they should join him in Canada.

In view of these arrangements, which were well known to the Masons in the locality of Batavia, it did not occur to the men who took this ill-advised action that anything like the excitement which followed would be occasioned. That the plan was entirely a local arrangement, we believe is conclusively shown by action of the Masonic Grand Bodies at that time.

The Grand Lodge of New York took no action in the matter until 1831, when it adopted resolutions reciting the facts and the misrepresentations and appointing a committee to ascertain and report at the next annual communication. In 1832 a supplemental report was adopted in which they deplored the action, characterizing it as "a violation alike of Masonic obligation and the law of the land," and asked for further time to complete their investigation.

The Grand Lodge of Vermont, October 7, 1829, issued an appeal in which it held itself guiltless of the different charges brought against the Fraternity in connection with the Morgan incident.

Other Grand Lodges took similar action. Perhaps the most effective and complete statement issued by Masons was the declaration of the Freemasons of Boston and vicinity, dated December 31, 1831, which was of great service in restoring the public mind to a normal state. This declaration is well worth consideration, and reveals not only a fine appreciation of the situation, by our best men, but also a splendid spirit of resolution to abide the results. It is as follows:

- "While the public mind remained in the high state of excitement to which it had been carried by the partial and inflammatory representations of certain offences committed by a few misguided members of the MASONIC INSTITUTION in a sister state, it seemed to the undersigned (residents of Boston and vicinity) to be expedient to refrain from a public DECLARATION of their principles and engagements as MASONS. But believing the time now to be fully come when their fellow citizens will receive with candor, if not with satisfaction, A SOLEMN AND UNEQUIVOCAL DENIAL OF THE ALLEGATIONS which, during the last five years, in consequence of their connection with the MASONIC FRATERNITY, have been reiterated against them, they respectfully ask permission to invite attention to the subjoined

DECLARATION:

Whereas, it has been frequently asserted and published to the world that in the several degrees of FREEMASONRY, as they are enforced in the United States, the candidate, in his initiation and subsequent advancement, binds himself by oath to sustain his Masonic brethren in acts which are at variance with the fundamental principles of morality and incompatible with his duty as a good and faithful citizen, in justice therefore to themselves, and with a view to establish TRUTH and expose IMPOSITION, the undersigned, many of us the recipients of every degree of Freemasonry known and acknowledged in this country, do most SOLEMNLY DENY the existence of any such obligations in the MASONIC INSTITUTION, so far as our knowledge respectively extends. And we as SOLEMNLY AVER that no person is admitted to the Institution without first being made acquainted with the nature of the obligations which he will be required to incur and assume.

FREEMASONRY secures its members in the freedom of thought and of speech, and permits each and everyone to act according to the dictates of his own conscience in matters of religion, and of his personal preferences in matters of politics; it neither knows, nor does it assume to inflict upon its erring members, however wide may be their aberration from duty, any penalties or punishments other than those of ADMONITION, SUSPENSION, and EXPULSION.

The obligations of the Institution require of its members a strict obedience to the laws of God and man. So far from being bound by any engagements inconsistent with the happiness and prosperity of the nation, every citizen who becomes a Mason is doubly bound to be true to his GOD, to his COUNTRY, and to his FELLOWMAN.

In the language of the Ancient Constitutions of the Order, which are printed and open for public inspection, and which are used as text books in all the lodges, he is required to keep and obey the MORAL LAW; to be a quiet and peaceful citizen, true to his government and just to his country.

MASONRY disdains the making of proselytes; she opens the portals of her asylum to those who seek admission with the recommendation of a character unspotted by immorality and vice. She simply requires of the candidate his assent to one great, fundamental, religious truth--THE EXISTENCE AND PROVIDENCE OF GOD; and a practical acknowledgement of those infallible doctrines for the government of life which are written by the finger of God on the heart of man.

ENTERTAINING such sentiments, as MASONS, as CITIZENS, as CHRISTIANS, and as MORAL MEN, and deeply impressed with the conviction that the MASONIC INSTITUTION has been, and may continue to be, productive of great good to their fellowmen; and having 'received the laws of the society, and its accumulated funds, in sacred trust for charitable uses,' the undersigned can neither renounce nor abandon it.

We most cordially unite with our Brethren of Salem and vicinity in the declaration and hope that, 'should the people of this country become so infatuated as to deprive Masons of their civil rights, in violation of their written constitutions, and the wholesome spirit of just laws and free governments, a vast majority of the Fraternity will still remain firm, confiding in God, and the rectitude of their intentions for consolation, under the trials to which they may be exposed."'

This declaration was written by Charles W. Moore, for many years Grand Secretary of our Grand Lodge. It was originally intended only for the Boston Encampment of Knights Templar. Later, at the earnest request of prominent Masons, it was submitted to the Grand Master, and subsequently signed by one thousand, four hundred and sixty-nine Masons from fifty four towns and districts in Massachusetts. Four hundred thirty-seven were of Boston.

More than six thousand Masons in New England subscribed to this declaration, which was given to the public on December 31, 1831.

M. W. Brother Gallagher, in commenting upon this declaration in an address given by him at Camden, Maine, on June 24, 1901, said:

- "It was the first heavy blow given to Anti-Masonry and with the political defeat in the Jackson campaign sounded the death knell of its existence. That famous declaration embodies and states concisely about all there is in the principles of the Masonic Order. Printed and read in our lodges, it would serve to assist in pursuing anew our journey in the paths of rectitude and Masonic virtue."