En:Buffalo Soldiers: Unterschied zwischen den Versionen

| Zeile 59: | Zeile 59: | ||

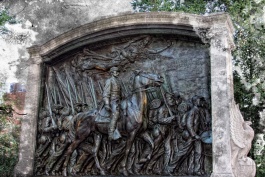

== Robert Gould Shaw Monument Boston. Gallery Sid Graves == | == Robert Gould Shaw Monument Boston. Gallery Sid Graves == | ||

All Photographies of [[En:Robert Gould Shaw|Robert Gould Shaw]] Monument Boston from [[Augustus Saint-Gaudens]] courtesy of [[Sid Graves]], Owner of Copyrights. | All Photographies of [[En:Robert Gould Shaw|Robert Gould Shaw]] Monument Boston from [[Augustus Saint-Gaudens]] courtesy of [[Sid Graves]], Owner of Copyrights. | ||

<gallery> | |||

<gallery widths="265" heights="350" perrow="3"> | |||

Bild:SidGravesBuffaloSoldiers1.jpg | Bild:SidGravesBuffaloSoldiers1.jpg | ||

Bild:SidGravesBuffaloSoldiers2.jpg | Bild:SidGravesBuffaloSoldiers2.jpg | ||

Version vom 15. August 2015, 14:56 Uhr

Bitte übersetzen

The Buffalo Soldiers

Source: Phoenixmasonry

By Frederic L. Milliken

Brother Joseph A. Walkes, Jr. tells us this:

“Prince Hall Freemasonry from its inception has played a major role is sustaining Black America. Nowhere is this more evident than in the wars fought by Blacks for America……the Black soldier brought with him not only his religion and his desire for true freedom, but his Masonry as well.”(1)

Prince Hall Masonry having risen from a Military Lodge has a tradition of chartering American Military Lodges that continues stronger than ever today where many Prince Hall Military Lodges can be found in Iraq and Afghanistan. And nowhere is this more illustrative than in the underappreciated mark left upon history by the post Civil War “Buffalo Soldiers.” For it is far from coincidence that these Brave men served with such distinction under such hardships with inferior supplies, equipment and horses. They did so because the Black soldier carried hand in hand with him into battle his religion and his Masonry.

The Buffalo Soldiers were all Black Cavalry Units consisting of the 9th and 10th Regiments (and sometimes the all Black 24th and 25th Infantry Regiments are included with the Cavalry). They received their name from Native American Indians with whom they fought many battles who said that the Black man’s hair resembled the mane of a Buffalo. The Spanish called them “Smoked Yankees”.

The 9th Regiment was formed by General P.H. Sheridan in New Orleans in August of 1866. The command of the 9th was awarded to Colonel Edward Hatch and almost immediately transferred to Fort Davis in Texas. Later it was to spend much time in New Mexico before going farther North.

The 10th Regiment was also formed in 1866 at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas and led by Regimental Commander Benjamin Grierson. Starting in Kansas and Oklahoma the 10th later spent much time in West Texas and Arizona.

These Regiments were the first Black soldiers commissioned for peace time military service. They were far from the first Black soldiers to fight for America as there were 5000 Black soldiers who fought for America’s independence in the Revolutionary War. By 1778 each of General George Washington’s brigades averaged 43 Black soldiers.

The Buffalo Soldiers fought and subdued hostile and marauding Indians, bandits, cattle rustlers, Mescalero’s, desperadoes, outlaws, bootleggers, comancheros and Mexican revolutionaries. They served as protectors of cattle drives, settlers, stage coaches and railroad workers. They sometimes carried the mail, strung telegraph line, built forts which became future large settlements and explored and mapped many unchartered areas of the West, especially Texas.

The Buffalo Soldiers fought and subdued hostile and marauding Indians, bandits, cattle rustlers, Mescalero’s, desperadoes, outlaws, bootleggers, comancheros and Mexican revolutionaries. They served as protectors of cattle drives, settlers, stage coaches and railroad workers. They sometimes carried the mail, strung telegraph line, built forts which became future large settlements and explored and mapped many unchartered areas of the West, especially Texas.

The heyday of the Buffalo soldiers was from 1867-1898 but honorable mention is given to the 9th & 10th Calvary Regiments activities through 1916. A general time line of the 9th & 10th Cavalry Regiments subduing of hostile Indians looks like this:

- 1860s and 1870s – Comanche & Kiowa Wars

- 1877-1886 – Apache War

- 1890-1891 – Pine Ridge Campaign, The Sioux Wars

The Buffalo soldiers, however, were not given enough credit for their tireless effort that went into policing South Texas and the Mexican Border with the constant harassments, looting, stealing and murder by gangs of desperadoes who would cross the Mexican border and elude pursuit when American troops had to stop at the Rio Grande. Mexican Revolutionaries often used South Texas as a refuge, robbing and pillaging in the process. Eventually the situation got so bad that American Presidents gave permission to cross the river into Mexico in pursuit and eventually in search and destroy missions.

This perhaps led to requests for the ferocious fighting Buffalo Soldiers to participate with Teddy Roosevelt in the Battle of San Juan Hill in 1898 and the campaign against Pancho Villa in 1916.

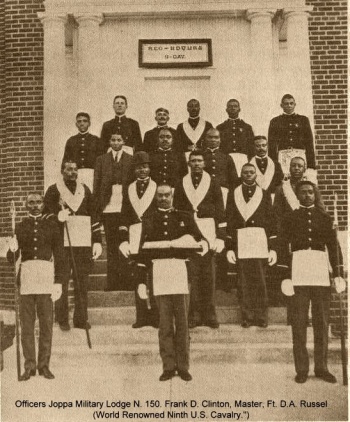

Walkes says that the first Military Masonic Lodge for The Buffalo Soldiers was granted UD by the Prince Hall Grand Lodge of Texas in 1883 to Baldwin Lodge, meeting in Camp Rice and nearby Fort Davis, Texas. “The Lodge was probably named after T.A. Baldwin, a Caucasian Captain, Commanding Officer of a Troop”, says Walkes who goes on to report that “ Baldwin was born in New Jersey and became a Brigadier-General and Commanding Officer of the 10th Cavalry. It was under his command that the 10th Cavalry, led by Black non-commissioned officers, saved Col. Teddy Roosevelt, a Mason, and his Rough Riders from being massacred at the famous charge up San Juan Hill”. (2 ) By 1885 Baldwin Lodge was given the number 16 and had moved to Arizona, at Forte Verde, Arizona in 1887, and then Fort Apache in 1889. It is recorded that Brother Benjamin F. Potts was installed as District Deputy Grand Master of Arizona which was designated the 6th Masonic District of The Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge of Texas. It was while at Fort Apache that Baldwin Lodge #16 found another Lodge Eureka #135, chartered by the Prince Hall Grand Lodge of Missouri. Baldwin Lodge #16 soon moved to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas in 1893-94, Fort Assinniboine, Chouteau County and then to Montana in 1895-97 whereupon it disappeared.

Such was the nature of Military Lodges. Most over time just ceased to exist without the benefit of written records to pass on to future generations the history of that Lodge. It was a result of the Military Life, constantly on the move and the large number of wounded Brethren and those who died in the service of their country.

After this initial chartering by the Prince Hall Grand Lodge of Texas, the rest of the Masonic Lodges chartered specifically for The Buffalo soldiers came from The Prince Hall Grand Lodge of Missouri. It is not known why this became a special mission of this Grand Lodge. It chartered so many Buffalo Soldiers Lodges that it became known as the “Mother Grand Lodge” for the 9th & 10th Black Calvary Units and the 24th & 25th Black Infantry Units. Alas, most of the records and proof of existence of these Lodges have been lost and it is only vague references to their existence that supports their widespread popularity among the Black military units. There were so many Lodges that it has been claimed that a significantly large number of Buffalo Soldiers were Prince Hall Masons.

Military Lodges

We do know about some of these Lodges. Eureka #135 which we have already met was the first Buffalo soldier Lodge chartered by The Grand Lodge of Missouri sometime before 1888. Then came Adventure Lodge #136 attached to the 9th Cavalry in Wingate, New Mexico, followed by Gillispie Lodge #140 with the 25th Infantry at Fort Missoula, Montana, later with the 9th Cavalry at Fort Du Chesne, Utah. Military Lodge #152 was next which started at Du Chesne but soon moved to Fort Grant, Arizona. Military Lodge #153 was organized at Fort Grant. Military Lodge #135 dedicated and installed Minnachuduza Military Lodge UD at Niobrora, Nebraska on May 27, 1906.

Interestingly Missouri’s District Deputy Grand Master, Brother W.H. Loving organized Manila Military Lodge #63 on March 5, 1906 and John M. McCarthy Lodge #50 in 1912 at Honolulu, Hawaii. The latter was attached to the 25th Infantry at Schofield Barracks. The Grand Lodge of Missouri would call these two Lodges their 20th Masonic District.

Of all these Lodges we have only one Lodge that has given posterity pictures. That was Joppa Lodge #150 with the 9th Cavalry at Fort Walla Walla, Washington, then Fort Riley, Kansas and finally The Philippines.

There is much to be proud of in the performance of the Buffalo Soldiers. They received eighteen Congressional Medals of Honor. Yet they operated with substandard equipment and sometimes were working in weather extremes for which they were inadequately outfitted. They constantly received old and worn out hand me down horses, often from the White 7th Cavalry. Many of their saddles had long since seen better days. William H. Leckie writes in his defining work “The Buffalo Soldiers”:

“Poor meals, like poor horses, were constant companions of Negro Troopers. The post surgeon at Fort Concho put it bluntly. The food was inferior to that provided at other posts. The bread was sour, beef of poor quality, and the canned peas not fit to eat. There were none of the staples common at other posts – molasses, canned tomatoes, dried apples, dried peaches, sauerkraut, potatoes, or onions. The butter was made of suet, and there was only enough flour for the officers. Certainly there were no visions of a sumptuous repast in the minds of worn-out troopers coming in to Concho after days or weeks in the field.”(3)

The life of a Buffalo soldier was hard and lonely. He was often out on patrol for weeks at a time in very desolate and isolated country. Discipline was harsh, recreation seldom available and prejudice and death always right around the corner. Yet the 9th & 10th Calvary units had the lowest desertion rate of any American military units. Morale was high. As Leckie reports, Buffalo Soldiers were ‘proud, tough and confident” (4) and ferocious combatants. Maybe what they had that other military units lacked was their religion and their Masonry always with them.

There are a few engagements that point out these qualities of the Buffalo Soldiers.

Robert Gould Shaw Monument Boston. Gallery Sid Graves

All Photographies of Robert Gould Shaw Monument Boston from Augustus Saint-Gaudens courtesy of Sid Graves, Owner of Copyrights.

The Battle of Fort Lancaster, Texas 1867

Captain Frohock and Fifty Eight Buffalo Soldiers hold off a force of 900 Indians, Mexicans and renegade White men. The continuous firing of .50 caliber Spencer repeating rimfire rifles and .44 Remington revolvers were instrumental in the Buffalo Soldiers winning this battle.

Battle of Kickapoo Springs, Texas May 20, 1870

Sergeant Emmanuel Stance is awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for his heroic action in a battle with Kickapoo Indians. He was the first African American to win his country’s highest military honor in the post civil War period.

Battle at Eagles Nest Crossing, Pecos River, Texas April, 1875

In what is believed to be the only instance of multiple Medal of Honor Awards in the same battle, three Seminole Negro Indian Scouts and three Buffalo Soldiers were awarded six Congressional Medals of Honor for their daring rescue of a wounded comrade while under heavy fire and pursuit.

The Hembrillo Battle April 6, 1880

Two Companies of Buffalo soldiers held off 150 Apache warriors led by Victorio at the site of the present day White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico. Reinforcements made this the largest battle of the Victorio War.

In the Spanish American War four Black Regiments fought with Teddy Roosevelt and His Rough Riders. The 10th Cavalry commanded by John J. Pershing was instrumental in the victory at San Juan Hill. Hereafter Col. Pershing was known as “Black Jack” Pershing because he was a White officer who respected and enjoyed leading Black troops. Black Jack Pershing went on to become a famous WWI General.

In 1916 Black Jack Pershing lead a year long campaign into Mexico in pursuit of Pancho Villa. Black Jack specifically requested for the 10th Calvary to be a big part of this venture.

Frank N. Schubert in a paper delivered at the 1998 conference of Army Historians in Bethesda, Maryland had these observations:

“Despite the fact that these groups shared the victory and despite the attention that gravitated toward TR, the post-battle spotlight shone brightly on the Buffalo Soldiers. Since the Reorganization Act of 1866, their regiments had mainly served in the remotest corners of the West. They had fought against the Comanches and Kiowa in the 1860s and 1870s and the Apaches between 1877 and 1886, and they had seen service in the Pine Ridge campaign of 1890–1891. Most of this duty had been performed in obscurity.”

“But Cuba was different. All eyes that were not on TR seemed to focus on the Buffalo Soldiers. For the first time they stood front and center on the national stage. A number of mainstream (that is, white) periodicals recounted their exploits, as nurses in the yellow fever hospital at Siboney as well as on the battlefield, and reviewed their history, mostly favorably.9 Books by black authors recounted the regiments’ service in Cuba and in previous wars and reminded those who cared to pay attention that the war with Spain did not represent the first instance in which black soldiers answered the nation’s call to arms.10 In an age of increasing racism that was hardening into institutionalized segregation throughout the South and affecting the lives of black Americans everywhere, the Buffalo Soldiers were race heroes. Black newspapers and magazines tracked their movements and reported their activities. Poetry, dramas, and songs all celebrated their service and valor.11 As Rayford Logan, dean of a generation of black historians—and my undergraduate adviser—later wrote, "Negroes had little, at the turn of the century, to help sustain our faith in ourselves except the pride that we took in the 9th and 10th Cavalry, the 24th and 25th Infantry. Many Negro homes had prints of the famous charge of the colored troops up San Juan Hill. They were our Ralph Bunche, Marian Anderson, Joe Louis and Jackie Robinson."(5)

Today we celebrate The Buffalo Soldiers with two attractions you can visit. The first is The Buffalo Soldiers National Museum, 1834 Southmore, Houston, TX 77004 – 713-942-8920, admission $2.00 pp.

The Buffalo Soldier Monument

The Second is THE BUFFALO SOLDIER MONUMENT at Fort Leavenworth Kansas. The idea for the sculpture came from General Colin Powell who was deputy commander at the Fort in 1981-82. In jogging around the post he observed that there was no tribute to the 10th Cavalry which was started at Fort Leavenworth. Lee W. Brubaker and Eddie Dixon, an artist from Lubbock, Texas created the statue. And Colin Powell returned in July of 1990 to dedicate the monument.

“Many 10th Cavalry soldiers attended the ceremony and proudly looked on as keynote speaker Gen. Powell addressed them and others in the audience. For many, this was a moment they had anticipated for years. Powell quoted from the last order issued by Col. Benjamin H. Grierson, the first regimental commander of the lOth Cavalry, to his black troops in 1888: "The officers and enlisted men have cheerfully endured many hardships and privations and in the midst of great dangers steadfastly maintained a most gallant and zealous devotion to duty...and they may well be proud of the record made, and rest assured that the hard work undergone in the accomplishment of such...valuable service to their country cannot fail, sooner or later, to meet with due recognition and reward."

General Powell at the dedication of the Buffalo Soldier memorial at Fort Leavenworth. Buffalo Soldiers was the name given by American Indians to the African Americans who served with the 10th Cavlary during the winning of the West.

Bibliography

- “Black Square & Compass”, Joseph A. Walkes, Jr. Page 65

- Ibid Page 67

- “The Buffalo Soldiers”, by William H. Leckie Pages 98 & 99

- Ibid Page99

- → “The Buffalo Soldiers AT San Juan Hill” by Frank N. Schubert

- → "The Buffalo Soldier Monument" by Anthony R Williams - BNET

Videos

<videoflash>WbcxZM32ZrQ</videoflash> <videoflash>LhMJN3wwc4c</videoflash> <videoflash>lnvSxxYQkIU</videoflash>