En: William Preston: Unterschied zwischen den Versionen

KKeine Bearbeitungszusammenfassung |

|||

| Zeile 1: | Zeile 1: | ||

== William Preston == | == William Preston == | ||

[[Datei:William Preston 1812.jpeg]] | |||

This distinguished Freemason was born at Edinburgh on July 28, 1742, Old Style, and Brother C. C. Hunt, of Iowa, points out that the date sometimes given as August 7, New Style, should be August 8, as the calendar error which was ten clays in 1582 had become eleven in the eighteenth century when the change was made in English-speaking countries He was the son of William Preston, Esq., Writer to the Signet, a Scottish legal term meaning an agent or attorney in causes in the Court of Sessions, and Helena Cumming. The elder Preston was a man of much intellectual culture and ability, and in easy circumstances, and took, therefore, pains to bestow upon his son an adequate education. He was sent to school at a very early age, and having completed his preliminary education in English under the tuition of Stirling, a celebrated teacher in Edinburgh, he entered the High School before he was six years old, and made considerable progress in the Latin tongue. | |||

From the High School he went to college, where he acquired acknowledge of the rudiments of Greek. After the death of his father he retired from college, and became the amanuensis of that celebrated linguist, Thomas Ruddiman, to whose friendship his father had consigned him. Ruddiman having greatly impaired and finally lost his sight by his intense application to his classical studies, Preston remained with him as his secretary until his decease. His patron had, however, previously bound young Preston to his brother, Walter Ruddiman, a printer, but on the increasing failure of his sight, Thomas Ruddiman withdrew Preston from the printing-office, and occupied him in reading to him and translating such of his works as were not completed, and ia correcting the proofs of those that were in the press. Subsequently Preston compiled a catalogue of Ruddiman's books, under the title of Bibliotheca Ruddimana, which is said to have exhibited much literary ability. | From the High School he went to college, where he acquired acknowledge of the rudiments of Greek. After the death of his father he retired from college, and became the amanuensis of that celebrated linguist, Thomas Ruddiman, to whose friendship his father had consigned him. Ruddiman having greatly impaired and finally lost his sight by his intense application to his classical studies, Preston remained with him as his secretary until his decease. His patron had, however, previously bound young Preston to his brother, Walter Ruddiman, a printer, but on the increasing failure of his sight, Thomas Ruddiman withdrew Preston from the printing-office, and occupied him in reading to him and translating such of his works as were not completed, and ia correcting the proofs of those that were in the press. Subsequently Preston compiled a catalogue of Ruddiman's books, under the title of Bibliotheca Ruddimana, which is said to have exhibited much literary ability. | ||

| Zeile 104: | Zeile 103: | ||

Masonic Service Association of North America | Masonic Service Association of North America | ||

{{SORTIERUNG:Preston}} | |||

[[Kategorie:Personalities|Preston]] | |||

Version vom 7. August 2015, 08:52 Uhr

William Preston

This distinguished Freemason was born at Edinburgh on July 28, 1742, Old Style, and Brother C. C. Hunt, of Iowa, points out that the date sometimes given as August 7, New Style, should be August 8, as the calendar error which was ten clays in 1582 had become eleven in the eighteenth century when the change was made in English-speaking countries He was the son of William Preston, Esq., Writer to the Signet, a Scottish legal term meaning an agent or attorney in causes in the Court of Sessions, and Helena Cumming. The elder Preston was a man of much intellectual culture and ability, and in easy circumstances, and took, therefore, pains to bestow upon his son an adequate education. He was sent to school at a very early age, and having completed his preliminary education in English under the tuition of Stirling, a celebrated teacher in Edinburgh, he entered the High School before he was six years old, and made considerable progress in the Latin tongue.

From the High School he went to college, where he acquired acknowledge of the rudiments of Greek. After the death of his father he retired from college, and became the amanuensis of that celebrated linguist, Thomas Ruddiman, to whose friendship his father had consigned him. Ruddiman having greatly impaired and finally lost his sight by his intense application to his classical studies, Preston remained with him as his secretary until his decease. His patron had, however, previously bound young Preston to his brother, Walter Ruddiman, a printer, but on the increasing failure of his sight, Thomas Ruddiman withdrew Preston from the printing-office, and occupied him in reading to him and translating such of his works as were not completed, and ia correcting the proofs of those that were in the press. Subsequently Preston compiled a catalogue of Ruddiman's books, under the title of Bibliotheca Ruddimana, which is said to have exhibited much literary ability.

After the death of Ruddiman, Preston returned to the printing-office where he remained for about a year; but his inclinations leading him to literary pursuits, he, with the consent of his master, repaired to London in 1760, having been furnished with several letters of introduction by his friends in Scotland. Among them was one to William Strahan, the Kings Printer, in whose service, and that of his son and successor, he remained for the best years of his life as a corrector of the press, devoting himself, at the same time, to other literary vocations, editing for many years the London Chronicle, and furnishing materials for various periodical publications. Preston's critical skill as a corrector of the press led the literary men of that day to submit to his suggestions as to style and language; and many of the most distinguished authors who were contemporary with him honored him with their friendship. As an evidence of this, there were found in his library, at his death, presentation copies of their works, with their autographs, from Gibbon, Hume, Robertson, Blair, and many others.

It is, however, as a distinguished instructor of the Masonic Ritual and as the founder of a system of lectures which still retain their influence, that William Preston the more especially claims our attention. Stephen Jones, the disciple and intimate friend of Preston, published in 1795, and in the Freemasons Magazine, a sketch of Preston's life and labors; and as there can be no doubt, from the relations of the author and the subject, of the authenticity of the facts related, we shall not hesitate to use the language of this contemporary sketch, interpolating such explanatory remarks as we may deem necessary.

Soon after Preston's arrival in London, a number of Brethren from Edinburgh resolved to institute a Freemasons' Lodge in that city, under the sanction of a Constitution from Scotland; but not having succeeded in their application, they were recommended by the Grand Lodge of Scotland to the Ancient Lodge in London, which immediately granted them a Dispensation to form a Lodge and to make Freemasons. They accordingly met at the White Hart in the Strand, and Preston was the second person initiated under that Dispensation. This was in 1762. Lawrie records the application as having been in that year to the Grand Lodge of Scotland. It thus appears that Preston was made a Freemason under the Dermott system. It will be seen, however, that he subsequently went over to the older Grand Lodge.

The Lodge was soon after regularly constituted by the officers of the Ancient Grand Lodge in person. Having increased considerably in numbers, it was found necessary to remove to the Horn Tavern in Fleet Street, where it continued some time, till, that house being unable to furnish proper accommodations, it was removed to Scots Hall, Blackfriars.

Here it continued to flourish about two years, when the decayed state of that building obliged it to remove to the Half Moon Tavern, Cheapside, where it continued to meet for a considerable time. At length Preston and some others of the members having joined the Lodge, under the older English Constitution, at the Talbot Inn, in the Strand, they prevailed on the rest of the Lodge at the Half Moon Tavern to petition for a Constitution. Lord Blaney at that time Grand Master, readily acquiesced with the desire of the Brethren, and the Lodge was soon after constituted a second time, in ample form, by the name of the Caledonian Lodge, then No. 325, but now 134. The ceremonies observed, and the numerous assembly of respectable Brethren who attended the Grand Officers on that occasion, were long remembered to the honor of the Lodge.

This circumstance, added to the absence of a very skillful Freemason, to whom Preston was attached and who had departed for Scotland on account of his health, induced him to turn his attention to the Masonic lectures; and to arrive at the depths of the science, short of which he did not mean to stop, he spared neither pains nor expense.

Preston's own remarks on this subject, in the introduction to his Illustrations of Masonry, are well worth the perusal of every Brother who intends to take office.. "When," says he, "I first had the honor to be elected Master of a Lodge, I thought it proper to inform myself fully of the general rules of the society, that I might be able to fulfil my own duty, and officially enforce obedience in others. The methods which I adopted, with this view, excited in some of superficial knowledge an absolute dislike of what they considered as innovations; and in others, who were better informed, a jealousy of pre-eminence, which the principles of Masonry ought to have checked. Notwithstanding; these discouragements, however, I persevered in my intention of supporting the dignity of the society, and of discharging with fidelity the trust reposed in me." Freemasonry has not changed. We still too often find the same mistaking of research for innovation, and the same ungenerous jealousy of pre-eminence of which Preston complains.

Wherever instruction could be acquired, thither Preston directed his course; and with the advantage of a retentive memory, and an extensive Masonic connection, added to a diligent literary research, he so far succeeded in his purpose as to become a competent master of the subject. To increase the knowledge he had acquired, he solicited the company and conversation of the most experienced Freemasons from foreign countries; and, in the course of a literary correspondence with the Fraternity at home and abroad, made such progress in the mysteries of the art as to become very useful in the connections he had formed. He was frequently heard to say, that in the ardor of his inquiries he had explored the abodes of poverty and wretchedness, and, where it might have been least expected, acquired very valuable scraps of information. The poor Brother in return, we are assured, had no cause to think his time or talents ill bestowed. He was also accustomed to convene his friends once or twice a week, in order to illustrate the lectures; on which occasion objections were started, and explanations given, for the purpose of mutual improvement. At last, with the assistance of some zealous friends, he was enabled to arrange and digest the whole of the first lecture.

To establish its validity he resolved to submit to the society at large the progress he had made; and for that purpose he instituted, at a very considerable expense, a grand gala at the Crown and Anchor Tavern, in the Strand, on Thursday, May 21, 1779, which was honored with the presence of the then Grand Officers, and many other eminent and respectable Brethren. On this occasion he delivered an oration on the Institution, which, having met with general approbation, was afterward printed in the first edition of the Illustrations of Masonry, published by him the same year.

Having thus far succeeded in his design, Preston determined to prosecute the plan he had formed, and to complete the lectures. He employed, therefore, a number of skillful Brethren, at his own expense, to visit different town and country Lodges, for the purpose of gaining information; and these Brethren communicated the result of their visits at a weekly meeting. When by study and application he had arranged his system, he issued proposals for a regular course of lectures on all the Degrees of Freemasonry, and these were publicly delivered by him at the Miter Tavern, in Fleet Street, in 1774.

For some years afterward, Preston indulged his friends by attending several schools of instruction, and other stated meetings, to propagate the knowledge of the science, which had spread far beyond his expectations, and considerably enhanced the reputation of the society. Having obtained the sanction of the Grand Lodge, he continued to be a zealous encourager and supporter of all the measures of that assembly which tended to add dignity to the Craft, and in all the Lodges in which his name was enrolled, which were very numerous, he enforced a due obedience to the laws and regulations of that Body.

By these means the subscriptions to the charity became much more considerable; and daily acquisitions to the society were made of some of the most eminent and distinguished characters. At last he was invited by his friends to visit the Lodge of Antiquity, No. 1, then held at the Miter Tavern, in Fleet Street, when on June 15, 1774, the Brethren of that Lodge were pleased to admit him a member, and, what was very unusual, elected him Master at the same meeting.

He had been Master of the Philanthropic Lodge at the Queen's Head, Gray's-inn-gate, Holborn, for over six years, and of several other Lodges before that time. But he was now taught to consider the importance of the first Master under the English Constitution; and he seemed so regret that some eminent character in the walks of life had not been selected to support so distinguished a station. Indeed, this too small consideration of his own importance pervaded his conduct on all occasions; and he was frequently seen voluntarily to assume the subordinate offices of an assembly, over which he had long presided, on occasions where, from the absence of the proper persons, he had conceived that his services would promote the purposes of the meeting. To the Lodge of antiquity he now began chiefly to confine his attention, and during his Mastership, which continued for some years, the Lodge increased in numbers and improved in its finances. That he might obtain a complete knowledge of the state of the society under the English Constitution, he became an active member of the Grand Lodge, was admitted a member of the Hall Committee, and during the secretaryship of Thomas French, under the auspices of the Duke of Beaufort, then Grand Master, had become a useful assistant in arranging the general regulations of the society, and reviving the foreign and country correspondence. Having been appointed to the office of Deputy Grand Secretary under James Heseltine, he compiled, for the benefit of the charity, the History of remarkable Occurrences, inserted in the first two publications of the Freemasons' Calendar: prepared for the press an Appendia; to the Book of Constitutions, and attended so much to the correspondence with the different Lodges as to merit the approbation of his patron. This enabled him, from the various memoranda he had made, to form the history of Freemasonry, which was afterward printed in his Illustrations. The office of Deputy Grand Secretary he afterward resigned.

An unfortunate dispute having arisen in the Society in 1777, between the Grand Lodge and the Lodge of Antiquity, in which Preston took the part of the Lodge and of his private friends, his name was ordered to be erased from the Hall Committee; and he was afterward, with a number of gentlemen, members of that Lodge, expelled. The treatment he and his friends received at that time was circumstantially narrated in a well-written pamphlet, printed by Preston at his own expense, and circulated among his friends, but never published, and the leading circumstances were recorded in some of the later editions of the Illustrations of Masonry. Ten years afterward, however, on a reinvestigation of the subject in dispute, the Grand Lodge was pleased to reinstate Preston, with all the other members of the Lodge of Antiquity, and that in the most handsome manner, at the Grand Feast in 1790, to the general satisfaction of the Fraternity.

During Preston's exclusion, he seldom or ever attended any of the Lodges, though he was actually an enrolled member of a great many Lodges at home and abroad, all of which he politely resigned at the time of his suspension, and directed his attention to his other literary pursuits, which may fairly be supposed to have contributed more to the advantage of his fortune.

So much of the life of Preston we get from the interesting sketch of Stephen Jones. To other sources we must look for a further elucidation of some of the circumstances which he has so concisely related. The expulsion from the Order of such a man as Preston was a disgrace to the Grand Lodge which inflicted it. It was, to use the language of Doctor Oliver, who himself, in after times, had undergone a similar act of injustice, "a very ungrateful and inadequate return for his services."

The story was briefly this: It had been determined by the Brethren of the Lodge of Antiquity, held on December 17, 1777, that at the Annual Festival on Saint John's day, a procession should be formed to Saint Dunstan's Church, a few steps only from the tavern where the Lodge was held; a protest of a few of the members was entered against it on the day of the festival. In consequence of this only ten members attended, who, having clothed themselves as Freemasons in the vestry room, sat in the same pew and heard a sermon, after which they crossed the street in their gloves and aprons to return to the Lodge-room.

At the next meeting of the Lodge, a motion was made to repudiate this act; and while speaking against it, Preston asserted the inherent privileges of the Lodge of Antiquity, which, not working under a Warrant of the Grand Lodge, was, in his opinion, not subject in the matter of processions to the regulations of the Grand Lodge. It as for Maintaining this opinion, which whether right or wrong,- was after all only an opinion, Preston u as, under circumstances which exhibited neither magnanimity nor dignity on the part of the Grand Lodge, expelled from the Order. One first unhappy result of this act of oppression was that the Lodge of Antiquity severed itself from the Grand Lodge, and formed a rival Body under the style of the Grand Lodge of England South of the River Treatt, acting under authority from the Lodge of All England at York.

But ten years afterward, in 1787, the Grand Lodge saw the error it had committed, and Preston was restored with all his honors and dignities and the new Grand Lodge collapsed. And non, while the name of Preston is known and revered by all who value Masonic learning, the names of all his bitter enemies, with the exception of Noorthouch, have sunk into a well-deserved oblivion. Preston had no sooner been restored to his Masonic rights than he resumed his labors for the advancement of the Order. In 1787 he organized the Order of Harodim, which see, a society in which it was intended to thoroughly teach the lectures which he had prepared. Of this Order some of the most distinguished Freemasons of the day became members, and it is said to have produced great benefits by its well-devised Plan of Masonic instruction.

But William Preston is best known to us by his invaluable work entitled I Illustrations of Masonry. The first edition of this work was published in 1772. Although it is spoken of in some resolutions of a Lodge, published in the second edition, as "a very ingenious and elegant pamphlet," it was really a work of some size, consisting, in its introduction and text, of 288 pages. It contained an account of the Grand Gala, or banquet, given by the author to the Fraternity in May, 177 , when he first proposed his system of lectures. This account was omitted in the second and all subsequent editions "to make room for more useful matter." The second edition, enlarged to 324 pages, was published in 1775, and this was followed by others in 1776, 1781, 1788, 1792, 1799, 1801, and 1812.

There were other editions, for Wilkie calls his 1801 edition the tenth, and the edition of 1819, the last published by the author, is called the twelfth. The thirteenth and fourteenth editions were published of ter the author's death, with additions-the former by Stephen Jones in 1891, and the latter by Doctor Oliver in 1829. Other English editions have been subsequently published, one edited by Doctor Oliver in 1829. The work was translated into German. and two editions published, one in 1776 and the other in 1780. In America, two editions were published in 1804, one at Alexandria, in Virginia, and the other, with numerous important additions, by George Richards, at Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Both claim, on the title-page, to be the "first American edition"; and it is probable that both works were published by their respective editors about the same time, and while neither had any knowledge of the existence of a rival copy.

Preston died, after a long illness, in Dean Street. Fetter Lane, London, on April 1, 1818, at the age of seventy-six, and was buried in Saint Paul's Cathedral In the latter years of his life he seems to have taken no active public part in Freemasonry, for in the very full account of the proceedings at the Union in 1813 of the two Grand Lodges, his name does not appear as one of the actors, and his system was then ruthlessly surrendered to the newer but not better one of Doctor Hemming. But he had not lost his interest in the Institution which he had served 80 well and so long, and by which he had been so well requited.

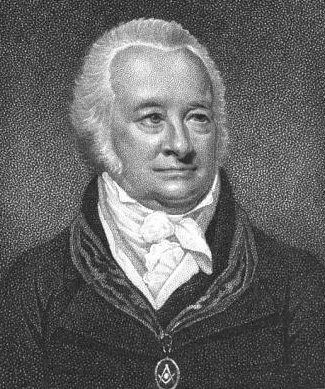

For he bequeathed at his death �300 in Consols, a contraction for consolidated annuities, a British government security, the interest of which was to provide for the annual delivery of a lecture according to his system. He also left �500 to the Royal Freemasons Charity, for female children, and a like sum to the General Charity Fund of the Grand Lodge. He had a wife and grandchildren and left behind him his name as 3 great Masonic teacher and the memory of his services to the Craft. Jones's edition of his Illustrations contains an excellently engraved likeness of him by Ridley, from an original portrait said to be by S. Drummond, Royal Academician. There is an earlier engraved likeness of him in the Freemasons Magazine for 1795, from a painting known to be by Drummond, and taken in 1794. They present the differences of features which may be ascribed to a lapse of twenty-six years. The latter print was said, by acquaintances, to be an excellent likeness.

The Records of Tile Lodge of Antiquity, No. 2, have been published in two volumes bearing that title, the first in 1911 edited by Brother W. Harry Rylands and the second in 1926 by Brother C. W. Firebrace who has also supervised the publication in 1928 of a second edition of the first volume. These splendid works contain much valuable information about William Preston whose Masonic career was so intimately associated with this famous Lodge.

- Source: Mackey's Encyclopedia of Freemasonry

William Preston

When we hear the name of William Preston we are at once reminded of the Preston lectures in Freemasonry, It is to Preston that we are indebted for what was the basis of our Monitors of the present day. The story of his literary labors in the interest of the Craft, and how they aided in making Freemasonry one of the leading educational influences during the closing decades of the eighteenth century, is one of absorbing interest to every member of the Fraternity.

William Preston was born in Edinburgh, Scotland, August 7th (old style calendar, July 28th), 1742. His father was a "Writer to the Signet," a law agent peculiar to Scotland and formerly eligible to the bench, therefore a man of much educational standing. He naturally desired to give his son all the advantages which the schools of that day afforded, and young Preston's education was begun at an early age. He entered high school before he was six years old.

After the death of his father Preston withdrew from college and took employment as secretary to Thomas Ruddiman, the celebrated linguist, whose failing eyesight made it necessary for Preston to do much research work required by Ruddiman in his classical and linguistic studies. At the demise of Thomas Ruddiman, Preston became a printer in the establishment of Walter Ruddiman, a brother of Thomas, to whom he had been formerly apprenticed.

Evidence of Preston's literary ability was first shown when he compiled a catalog of Thomas Ruddiman's books. After working in the printing office for about a year, a desire to follow his literary inclinations prevailed and, well supplied with letters of introduction, he set out for London in 1760. One of these letters was addressed to William Stranhan, the King's Printer, with whom Preston secured a position, remaining with Stranhan and his son for many years.

Preston possessed an unquenchable desire for knowledge. As was common to the times in which he lived, "man worketh from sun to sun." The eight-hour day, if known at all, was a rarity, and Preston supplanted his earlier education by study after his twelve-hour working day was over. The critical skill exercised in his daily vocation caused literary men of the period to call upon him for assistance and advice. His close association with the intellectual men of his time was attested by the discovery after his death of autographed presentation copies of the works of Gibbon, Hume, Robertson, Blair,and others.

The exact date of Preston's initiation is not known, but it occurred in London in 1762 or 1763. It has been satisfactorily ascertained that his Mother Lodge was the one meeting at the White Hart Tavern in the Strand. This Lodge was formed by a number of Edinburgh Masons Sojourning in London, who, after being refused an application for a Charter by the Grand Lodge of Scotland, accepted a suggestion of the Scottish Grand Body that they apply to the ancient Grand Lodge of London. The Ancients granted a dispensation to these brethren on March 2nd, 1763, and it is claimed by one eighteenth century biographer that Preston was the second person initiated under that dispensation. The minutes of the Athol (Ancient) Grand Lodge show that Lodge No. 111 was Constituted on or about April 20th, 1763, William Leslie, Charles Halden and John Irwin being the Master and Wardens, and Preston's name was listed as the twelfth among the twenty-two on the roll of membership.

It was not uncommon in those times (and the custom still prevails in England, Canada, and other countries, and among several Grand Jurisdictions in the United States) for Masons to belong to more than one Lodge, and Preston and some other members of his Mother Lodge also became members of a Lodge Chartered by the Moderns, which met at the Talbot Tavern in the Strand. These brethren prevailed upon the membership of Lodge No. 111, which in the meantime had moved its meeting place to the Half Moon Tavern, to apply to the Modern Grand Lodge for a Charter. Lord Blayney, then Grand Master, granted a Charter to the members of Lodge No. 111, which was Constituted a second time, on November 15th, 1764, taking the name Caledonian Lodge No. 325. This Lodge is still in existence, being No. 134 on the present registry of the United Grand Lodge of England.

The constitution of the new Caledonian Lodge was a noteworthy event because of the presence of many prominent Masons of the day. The ceremonies and addresses on this occasion made a deep impression upon Preston, being among the factors which induced him to make a serious study of Freemasonry. The desire to know more of the Fraternity, its origin and its teachings, was intensified when he was elected Worshipful Master, for, as he said: "When I first had the honor to be elected Master of a Lodge, I thought it proper to inform myself fully of the general rules of the Society, that I might be able to fulfill my own duty and officially enforce obedience in others. The methods which I adopted, with this view, excited in some of superficial knowledge an absolute dislike of what they considered innovations; and in others who were better informed, a jealously of preeminence, which the principles of Masonry ought to have checked."

Preston entered into an extensive correspondence with Masons at home and abroad, extending his knowledge of Craft affairs and gathering the material which later found expression in his best known book, "Illustrations of Masonry." He delved into the most out of the way places in search of Masonic lore and wisdom, by which the Craft was greatly benefitted.

Preston was a frequent visitor to other Lodges. He was asked to visit the Lodge of Antiquity No. 1, one of the four Old Lodges which formed the Grand Lodge of England in 1717. On that occasion, June 15, 1774, he as elected a member of the Lodge and also Worshipful Master at the same meeting. This unusual action is additional evidence of the regard in which he was held by the Brethren of his day. While he had been Master of several other Lodges, he gave of his best in time and energy to the Lodge of Antiquity, which thrived greatly under his leadership.

He became an active member of the Grand Lodge, serving on its Hall Committee, a committee appointed in 1773 for the purpose of superintending the erection of the Masonic Hall which had been projected, and he was later appointed Deputy Grand Secretary under James Heseline. In this capacity he revived the foreign and country correspondence of the Grand Lodge, an easy matter for him because of his extensive personal correspondence with Brethren outside of London.

In 1777 occurred an event which was momentous in the Masonic affairs of the period. On account of the mock and satirical processions formed by rival societies the Modern Grand Lodge of England had forbidden its Lodges and Members to appear in public processions in regalia. The Lodge of Antiquity, on December 17th, 1777, resolved to attend church services in a body on St. John's Day, the following 27th, selecting St. Dinstan's Church, only a short distance across the street from where the Lodge met. Some of the members protested, saying it was contrary to Grand Lodge regulations, with the result that only ten attended, these donning gloves and aprons in the church vestry, and then entering to hear the sermon. At the conclusion of the services they returned to the Lodge without first removing their Masonic clothing. This action was cause for debate at the next meeting of the Lodge in which Preston expressed the opinion that the Lodge of Antiquity had never surrendered its rivileges and prerogatives when it participated in the formation of the Grand Lodge in 1717, and held that it could parade as it did in 1694. The Grand Lodge, however, could not afford to overlook such an opinion, especially when expressed by the leading Masonic Scholar of the day, and consequently Preston was expelled.

Because of this action of the Grand Lodge of Moderns, the Lodge of Antiquity severed its connection with body, after dismissing from its membership three brethren who had made the original complaint against Preston, entered in relations with the revived Grand Lodge of All England at York, and formed what was known as the "Grand Lodge of England South of the River Trent." The controversy with the Grand Lodge of Moderns was settled in 1787, and Preston was reinstated, all his honors and dignities restored, whereupon he resumed his Masonic activities. He organized the Order of Harodim, a Society of Masonic Scholars, in which he taught his lectures and through this medium the lectures came to America and became the foundation for our Monitors.

To fully grasp the significance of preston's labors we must understand the conditions in England at the time he lived. The seventeenth century had been one of marked differences of opinion on the subjects of government, religion and economic conditions. The eighteenth century, following the accession of Prince George of Hanover to the throne of England as King George I, witnessed an era of peace and prosperity in that country. With the exception of the wars against the French and later the Revolution in America, England met no obstacles in her conquests of trade. The strife of the opening years of the century calmed down, and the people became adjusted to their new conditions. It became a period of formalism. Literature, which thrived under the patronage of the wealthy, partook of an ancient classical nature, spirit being subordinated to form and style. Detailed perfection of form was insisted upon in every activity, and undoubtedly the insistence for a letter-perfect ritualism, still so apparent in Freemasonry, had its origin in the closing years of the eighteenth century.

While the well-to-do classes lived in comfort and ease, the laboring and farming classes had not yet entirely emerged from the adverse conditions confronting them for so many decades. True, the cessation of wars, and the development of domestic and foreign trade also had an influence in the circles not actively participating in the new development. A spirit of freedom and independence continued to express itself. Public education as we know it today, however, did not then exist. The schools were for the children of the wealthy only, being conducted by private interests and requiring the payment of tuition beyond the purse of the common people. Yet, education was eagerly sought. Knowledge was looked upon as the key which would unlock the door to intellectual and spiritual independence.

While Preston began his schooling at an early age, even with his excellent start he extended his education only by diligent work and the burning of much midnight oil. Imbued with the spirit of the day, he was anxious to place the available knowledge of the times before his fellow men. Therefore, when he discovered a vast body of traditional and historical lore in the old documents of the Craft, he naturally seized upon the opportunity of modernizing the ritual in such a way as to make accessible a rudimentary knowledge of the arts and sciences to the members of the Fraternity.

From 1765 to 1772 Preston engaged in personal research and correspondence with Freemasons at home and abroad, endeavoring to learn all he could about Freemasonry and the arts it encouraged. These efforts bore fruit in the form of his first book, entitled: "Illustrations of Masonry," published in 1772. He had taken the old lectures and work of Freemasonry, revised them and placed them in such form as to receive the approval of the leading members of the Craft. Encouraged by their favorable reception and sanctioned by the Grand Lodge, Preston employed, at his own expense, lecturers to travel throughout the kingdom and place the lectures before the lodges. New editions of his book were demanded, and up to the present time it has gone through twenty editions in England, six in America, and several more in various European languages.

After his death, on April 1st, 1818, it was found that Preston had provided a fund of three hundred pounds sterling in British Consuls (British Government Securities, the word being abbreviated from "Consolidated Annuities"), the interest from this fund to be set aside for the delivery of the Preston lectures once each year. The appointment of a Lecturer was left to the Grand Master. These lectures were abandoned about 1860, chiefly for the reason that they had been superseded by the lectures of Hemming in the approved work of the United Grand Lodge of England, when that body was formed by the reunion of the Ancient and Moderns in 1813. The Preston work still survives, however, in the United States, although greatly modified by such American Ritualists as Webb, Cross, Barney and others.

Had Preston not attained Masonic eminence through his efforts in other fields, his work in revising the lectures alone would entitle him to the plaudits and gratitude of the Craft. Considering these old lectures in the light of our present day knowledge, and granting that they might be corrected and revised, it must be remembered that Preston's work was a tremendous step forward when we consider the spirit and conditions of his day. He was one of the first men to influence a change from the social and convivial standards which prevailed in the old lodges, and to make them centers for more practical and enduring efforts. His own progress in the Craft is an illustration of its democracy, and an illustration of the equality of opportunity existing for those who will apply themselves to the problems confronting the Fraternity in our own times. From a position as the youngest Entered Apprentice standing in the North East corner of his lodge, he progressed step by step until he reached a place where he was recognized as the foremost Masonic Scholar of his generation. While he did not wear the purple of the Modern Grand Lodge in its highest stations, his contemporaries who had that honor have been forgotten, while the name of William Preston is still preeminent in the annals of Freemasonry.

Equality of opportunity, as Freemasonry stands for it, means equality of opportunity for service. The honors of office are not the Masonic test of service. He who contributes to the Mason's search for light, light that will enable the Craftsman to more intelligently and efficiently serve his God, his Country, his Neighbor, his Family and Himself is rendering the most enduring quality of service. This was true in Preston's time. It is equally true in ours. Fortunate is the lodge that has a modern Preston in its membership, who seeks to lead the Craft in its clearer understanding of the symbolism and teachings of Freemasonry to the end that Freemasons of today may sustain in the high standard of effective and unselfish service to mankind which has characterized and distinguished the Fraternity in the generations and ages gone.

Source: Short Talk Bulletin - Feb. 1923

Masonic Service Association of North America