En: Joseph Brant

Joseph Brant - A Masonic Legend

by Dr David Harrison

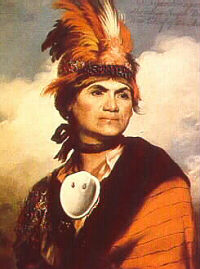

The story of Joseph Brant, the Mohawk ‘American Indian’ who fought for the Loyalists during the American War of Independence has been retold by the Iroquois peoples of the Six Nations and American Freemasons for centuries, and today Brant is featured in many Masonic Histories and is the topic of many websites. The story that is the most endearing is how Brant, a Mohawk chief, witnessed an American prisoner do a Masonic sign and spared the life of his fellow Mason. This action went down in history, and Brant became the embodiment of the ‘noble savage’ to Victorian England. This article will explain the events leading up to this event, and how Brant, in death, created even more controversy as the legends of his life grew and expanded.

Thayendanegea

Brant was born in 1742 in the area around the banks of the Ohio River, his Indian name was Thayendanegea, meaning ‘he places two bets’ and as a child he was educated at Moor’s Charity School for Indians in Lebanon, Connecticut, were he learned English and European History. He became a favourite of Sir William Johnson, who had taken Brant’s sister Molly as a mistress, though they were married later after Johnson’s wife died. Johnson was the British Superintendent for Northern Indian Affairs, and became close to the Mohawk people, and enlisted their allegiance in the French and Indian War of 1754-1763, with a young Brant taking up arms for the British.

Hiram's Cliftonian Lodge No. 814 in London

After the war Brant found himself working as an interpreter for Johnson. He had worked as an interpreter before the war and assisted in translating the prayer book and the Gospel of Mark into the Mohawk language, other translations included the Acts of the Apostles and a short history of the Bible, Brant having converted to Christianity, a religion which he embraced. Around 1775, after being appointed secretary to Sir William’s successor, Guy Johnson, Brant received a Captain’s commission in the British Army and set off for England, where he became a Freemason and confirmed his attachment to the British Crown. Brant was raised in Hiram's Cliftonian Lodge No. 814 in London, early in 1776, though his association with the Johnson’s may have been an influence in his links to Freemasonry. Guy Johnson had accompanied Brant on his visit to England, the Johnson family having Masonic links. Hiram’s Cliftonian Lodge had been founded in 1771, and during Brant’s visit to the lodge, it had met at the Falcon in Princes Street, Soho. The lodge was erased in 1782. Brant’s Masonic apron was, according to legend, presented to him by George III himself.

On his return to America, Brant became a key figure in securing the loyalty of other Iroquois tribes in fighting for the British against the ‘rebels’, and it was during the war that Joseph Brant entered into Masonic legend. After the surrender of the ‘rebel’ forces at the Battle of the Cedars on the St. Lawrence River in 1776, Brant famously saved the life of a certain Captain John McKinstry, a member of Hudson Lodge No.13 of New York, who was about to be burned at the stake. McKinstry, remembering that Brant was a Freemason, gave to him the Masonic sign of appeal which Brant recognized, an action which secured McKinstry’s release and subsequent good treatment. McKinstry and Brant remained friends for life, and in 1805 he and Brant together visited the Masonic Lodge in Hudson, New York, where Brant was given an excellent reception. Brant’s portrait now hangs in the lodge.

Lodge No. 11 at the Mohawk village at Grand River

Another story relating to Brant during the war has another ‘rebel’ captive named Lieutenant Boyd giving Brant a Masonic sign, which secured him a reprieve from execution. However, on this occasion, Brant left his Masonic captive in the care of the British, who subsequently had Boyd tortured and executed. After the war, Brant removed himself with his tribe to Canada, establishing the Grand River Reservation for the Mohawk Indians. He became affiliated with Lodge No. 11 at the Mohawk village at Grand River of which he was the first Master and he later affiliated with Barton Lodge No.10 at Hamilton, Ontario. Brant returned to England in 1785 in an attempt to settle legal disputes on the Reservation lands, were he was again well received by George III and the Prince of Wales.

After Brant’s death in 1807, his legend continued to develop, with numerous accounts of his life and his death being written. One such account lengthily entitled The Life of Captain Joseph Brant with An Account of his Re-interment at Mohawk, 1850, and of the Corner Stone Ceremony in the Erection of the Brant Memorial, 1886, celebrated Brant’s achievements and detailed that a certain Jonathan Maynard had also been saved by Brant during the war. Like McKinstry, Maynard, who later became a member of the Senate of Massachusetts, had been saved at the last minute by Brant who had recognized him giving a Masonic sign. Brant’s remains were re-interred in 1850 with an Indian relay, were a number of Warriors took turn in carrying his remains to the Chapel of the Mohawks, located in Brant’s Mohawk Village which is now part of the city of Brantford. Many local Freemasons were present, and his tomb was restored with an inscription paid for by them.

The legend of Brant saving his fellow Masons was examined by Albert C. Mackey in his Encyclopedia of Freemasonry in which he referred to a book entitled Indian Masonry by a certain Brother Robert C. Wright. In the book, Wright states that ‘signs given by the Indians could easily be mistaken for Masonic signs by an enthusiastic Freemason’. Using Wright’s claims that the Indians used similar Masonic signs or gestures within their culture, and these were mistaken by over enthusiastic Freemasons, Mackey was putting forward an argument that the stories of encounters with ‘Masonic’ Indians were perhaps in doubt. Mackey then put forward the question ‘is the Indian a Freemason’ before examining a number of historically Native American Indians that were Freemasons, including Joseph Brant and General Eli S. Parker, the Seneca Chief who fought in the American Civil War. Mackey concluded that ‘Thus from primitive and ancient rites akin to Freemasonry, which had their origin in the shadows of the distant past, the American Indian is graduating into Free and Accepted Masonry as it has been taught to us. It is an instructive example of the universality of human belief in fraternity, morality and immortality’. Mackey presented that the Indians, in recognizing the Universal ethos of Freemasonry within their own culture, were drawn to the Craft. Thus an understanding into Brant’s moralistic approach to fellow Freemasons who were prisoners during the war was being sought, his actions fascinating Masonic historians well into the twentieth century.

Metaphor for the Masonic bond

Brant became a symbol for Freemasonry, his story being used as a metaphor for the Masonic bond, a bond which became greater than the bond of serving ones country during wartime. Brant also came to represent a respect for the Native American Indian during a time when the USA was promoting the ‘manifest destiny’, an ethos which the United States government saw as God’s right for them to settle the Indian lands of the west. Brant’s myth even exceeded the traditional Victorian image of the ‘noble savage’, his meeting of other Freemasons while visiting London such as the writer James Boswell and Masonic members of the Hanoverian Household such as the Prince of Wales compounded this. Brant once said ‘My principle is founded on justice, and justice is all I wish for’, a statement which certainly conveyed his moralistic and Masonic ethos.

The above article originally appeared in MQ Magazine, issue 23, October 2007, copyright Dr David Harrison.