En:Prince Hall

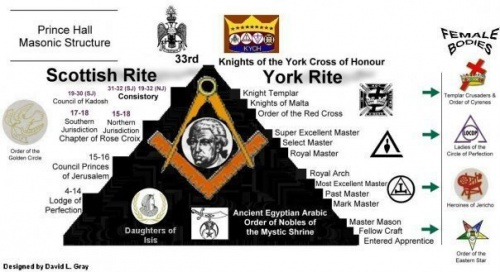

Prince Hall Masonry

Source: Mackey's Encyclopedia of Freemasonry

Ed. Note: The following article was written in the 1920s under the title Negro Masonry. It is presented for historical context purposes.

The subject of Lodges of colored persons, commonly called "Negro Lodges", has long been a source of contention in the United States. Not on account of the color of the members of these Lodges, but because of the supposed illegality of their origin and operation.

Prince Hall and thirteen other negroes were made Freemasons in a Military Lodge in the British Army then at Boston on March 6, 1775. When the Army was withdrawn these negroes applied to the Grand Lodge of England for a Charter and on the 20th of September, 1784 a Charter for a Masters Lodge was granted (although not received until 1787), to Prince Hall and others. All colored men, under the authority of the Grand Lodge of England. The Lodge bore the name of African Lodge No. 459 (later changed to No. 370), and was situated in the City of Boston. This Lodge, like many others, had little connection with the Grand Lodge of England for many years. and its registration, like many others, of Lodges still working, was stricken from the rolls of the United Grand Lodge of England when new lists were made in 1813.

African Lodge continued to operate and in 1827 they proclaimed "that with knowledge they possessed of Masonry, and as people of color by themselves, they were, and ought by right to be free and independent of other Lodges." Accordingly on June 18, 1827, they issued a protocol, in which they said: "We publicly declare ourselves free and independent of any Lodge from this day, and we will not be tributary or governed by any Lodge but that of our own." That is their present de facto status.

They soon after assumed the name of the Prince Hall Grand Lodge and issued Charters for the constitution of subordinates, and from it have proceeded the vast majority of the Lodges of colored persons now existing in the United States.

On March 12. 1947 the Grand Lodge of Massachusetts voted "to accept, approve and record" the report of a special committee of Past Grand Masters on this subject which closed its report with these words: "In conclusion your Committee believes that in view of the existing conditions in our country it is advisable for the official and organized activities of white and colored Freemasons to proceed in parallel lines, but organically separate and without mutually embarrassing demands or commitments. However, your Committee believes that within these limitations, informal cooperation and mutual helpfulness between the two groups upon appropriate occasions are desirable. " This was construed by some United States Grand Jurisdictions as recognition, though not actually so, and recognition of the Grand Lodge of Massachusetts w as withdraw n by some Grand Lodges and threatened by others and in 1949 the Grand Lodge of Massachusetts rescinded this resolution, not because they had changed their attitude, but they said because it seemed inexpedient and this action was taken only for the sake of harmony.

An apparently insurmountable barrier to recognition is the doctrine of exclusive Masonic territorial jurisdiction-only one Grand Lodge in any one state or territory. This rule is confined to the United States and Canada, but is strictly observed and enforced It prohibits invasion of occupied territory by any other Grand Lodge, not alone those of Negro origin and membership.

Since the writing of the article, a number of records of the Revolutionary Period have been discovered which have made it more clear why Negro, or Prince Hall, Masonry is clandestine in each and every American Grand Jurisdiction, and has been for more than a century. Prince Hall sent a petition for a Charter to the (Modern) Grand Lodge of Masons in 1777; according to Masonic law then in effect he should have submitted his petition to one or the other of the two already longest abolished Provincial Grand Lodges in Massachusetts, because he did not ask for a military warrant. Owing to war conditions, and to the chronic dilatoriness of the Modern Grand Lodge in responding to communications from America, the Charter was not received until 1787; yet during this inchoate period the self-styled African Lodge worked as a Lodge, made Masons, and helped to initiate the formation of other Negro Lodges, all in violation of Grand Lodge lau. The Charter itself became dormant, was rendered null and void, and was erased from the lists by the Grand Lodge of England.

In 1827 a group of Negroes made use of this piece of paper, which had become completely devoid of authority, to set up a new "Grand Lodge," and in which they declared themselves independent of any other Lodge-which declaration was in itself a plain proclamation that in their own eyes they were a clandestine society, and therefore not entitled by either Masonic or civil last to use the name "Masonic." Bodies acting according to the so-called "Prince Hall Constitutions" (which never existed) have continued to be clandestine ever since. In 1930 they had 37 Grand Lodges, with some 750,000 members in some 5,000 to 6,000 Lodges; by 1940, and owing to the depression, the membership had declined to about 500,000.

In 1899 the Grand Lodge of Washington, acting on a Report submitted by William H. Upton, declared its willingness to provide for Negro Lodges if a sufficient number of regularly-made Negro members could be found; but when one after another of the other Grand Lodges withdrew recognition, Washington rescinded its action. (See under PEACE AND HARMONY.) Upton elaborated his Report in book form under the title of Negro Masonry in 1902 the book is now obsolete because, 1. he did not at the time possess complete data

2. because his argument to the effect that Prince Hall and his associates had been regularly made and possessed a legitimate ritual in the beginning is irrelevant. Many Lodges have become clandestine in Britain and America after having worked for years as regular Lodges side the cases of Preston's Grand Lodge of England South of the River Kent, and the Lodges under the so-called Wigan Grand Lodge, and the many American Lodges which lost their charters during the Cerneau affair; and because

3. the whole structure of the argument which Lipton based on his theory of the Modern vs. the Ancient Grand Lodge is invalid.

See Negro Masonry in the United States, by Harold van Buren Voorhis; Henry Emmerson; New York; 1940; 132 pages; complete bibliography; it contains a chapter on Alpha Lodge, No. 116, Newark, N. J., which has all Negro members. (There are Lodges under the Grand Lodge of England with Negro membership.) Official History of Freemasonry among the Colored People in Narth America, by William H. Grimshaw; New York; 1903; 393 pages. Prince Hall and his Followers, by George W. Crawford (a Prince Hall member); New York; 1914; 96 pages. (Like other non-Masons Negro authors find it difficult to understand Masonic data; their statements of fact about actions taken by regular Grand Lodges may be checked against Grand Lodge Proceedings. Negro writers very seldom, for example, have their facts straight about actions taken at different times by the Grand Lodges of Massachusetts and of Washington.)

Prince Hall

Source: Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Freemasonry

Prince Hall Freemasonry derives from historical events in the early United States that led to a tradition of separate, predominantly African-American Freemasonry in North America.

In 1775, an African-American named Prince Hall[19] was initiated into an Irish Constitution military Lodge then in Boston, Massachusetts, along with fourteen other African-Americans, all of whom were free-born. When the military Lodge left North America, those fifteen men were given the authority to meet as a Lodge, form Processions on the days of the Saints John, and conduct Masonic funerals, but not to confer degrees, nor to do other Masonic work. In 1784, these individuals applied for, and obtained, a Lodge Warrant from the Premier Grand Lodge of England (GLE) and formed African Lodge, Number 459. When the UGLE was formed in 1813, all U.S.-based Lodges were stricken from their rolls – due largely to the War of 1812. Thus, separated from both UGLE and any concordantly recognised U.S. Grand Lodge, African Lodge re-titled itself as the African Lodge, Number 1 – and became a de facto "Grand Lodge" (this Lodge is not to be confused with the various Grand Lodges on the Continent of Africa). As with the rest of U.S. Freemasonry, Prince Hall Freemasonry soon grew and organised on a Grand Lodge system for each state.

Widespread segregation in 19th- and early 20th-century North America made it difficult for African-Americans to join Lodges outside of Prince Hall jurisdictions – and impossible for inter-jurisdiction recognition between the parallel U.S. Masonic authorities.

Prince Hall Masonry has always been regular in all respects except constitutional separation, and this separation has diminished in recent years. At present, Prince Hall Grand Lodges are recognised by some UGLE Concordant Grand Lodges and not by others, but they appear to be working toward full recognition, with UGLE granting at least some degree of recognition.[20] There are a growing number of both Prince Hall Lodges and non-Prince Hall Lodges that have ethnically diverse membership.

History

On March 6, 1775, an African American named Prince Hall was made a Master Mason in Irish Constitution Military Lodge No. 441, along with fourteen other African Americans: Cyrus Johnston, Bueston Slinger, Prince Rees, John Canton, Peter Freeman, Benjamin Tiler, Duff Ruform, Thomas Santerson, Prince Rayden, Cato Speain, Boston Smith, Peter Best, Forten Horward, and Richard Titley, all of whom apparently were free by birth. When the Military Lodge left the area, the African Americans were given the authority to meet as a Lodge, form Processions on the days of the Saints John, and conduct Masonic funerals, but not to confer degrees nor to do other Masonic work. These individuals applied for and obtained a Warrant for Charter from the Grand Lodge of England in 1784 and formed African Lodge #459.

Despite being stricken from the rolls (like all American Grand Lodges were after the 1813 merger of the Antients and the Moderns), the Lodge restyled itself as African Lodge #1 (not to be confused with the various Grand Lodges on the Continent of Africa), and separated itself from United Grand Lodge of England-recognized Masonry. This led to a tradition of separate, predominantly African American jurisdictions in North America, which are known collectively as Prince Hall Freemasonry. Widespread racism and segregation in North America made it impossible for African Americans to join many mainstream lodges, and many mainstream Grand Lodges in North America refused to recognize as legitimate the Prince Hall Lodges and Prince Hall Masons in their territory.

For many years both Prince Hall and "mainstream" Grand Lodges have had integrated membership, though in some Southern states this has been policy but not practice. Today, Prince Hall Lodges are recognized by the Grand Lodge of England (UGLE) as well as the great majority of state Grand Lodges in the US and many international Grand Lodges. While no Grand Lodge of any kind is universally recognized, at present, Prince Hall Masonry is recognized by some UGLE-recognized Grand Lodges and not by others, but appears to be working its way toward further recognition.[2] According to data compiled in 2008, 41 out of the 51 mainstream US Grand Lodges recognize Prince Hall Grand Lodges.

Notable members

There are many notable Masons who were affiliated with Prince Hall originated Grand Lodges.

Among the first Grand Masters, Prince Hall African Lodge #459:

- Prince Hall, Boston, Massachusetts, Grand Master 1791-1807

- Nero Prince, Boston, Massachusetts, Grand Master 1808

- George Middleton, Boston, Massachusetts, Grand Master 1809-1810. Commander, Bucks of America, a unit of black soldiers during the American Revolution. The unit received a flag from Governor John Hancock for its faithful service. Middleton was also a founder of the African Benevolent Society.

- Peter Lew, Dracut, Massachusetts, Grand Master 1811-1816, son of Barzillai Lew

- Sampson H. Moody, Grand Master 1817-1825

- John T. Hilton, Grand Master 1826-1827

- Walker Lewis, Lowell, Massachusetts, Grand Master 1829-1830

- Thomas Dalton, Boston, Massachusetts, Grand Master 1831-1832, son-in-law of Barzillai Lew

Videos

Links

- Prince Hall Freemasonry

- Prince Hall Freemasonry, Phylaxis Society (archive.org 2004)

- Prince Hall Revisited by Tony Pope, editor of the Australian & New Zealand Masonic Research Council's publications.

- The Black Heritage Trail The George Middleton House Boston African-American National Historic Site, archive.org 2006

- Museum of Afro-American History website George Middleton house and has photo of Bucks of America flag-for reference only}

- Some Famous Prince Hall Freemasons

- Famous Prince Hall Freemasons (PH Ohio, archive.org link)

- Ray Colemans article PDF (archive.org 2015)