Slowenien

Slowenien

Vier masonische Anläufe in fast 250 Jahren

Seit dem 18. Jahrhundert wurde auf dem Gebiet des heutigen Sloweniens viermal versucht, Logen zu gründen. Die ersten drei Anläufe dauerten immer nur kurze Zeit. Der vierte scheint gelungen zu sein: Im jungen unabhängigen demokratischen Slowenien existieren seit 1999 eine eigene (reguläre) Großloge und darüber hinaus zwei weitere, von denen eine Männer und Frauen aufnimmt (= Stand 2014). Von Rudi Rabe.

Erster Anlauf im 18. Jahrhundert

Einzelne slowenische Adelige finden bereits 1741 ihren Weg zu deutschen Logen in Bayreuth; andere später auch nach Wien, Freiburg, Triest, Prag und Budapest; mit Ausnahme von Bayreuth sind das damals habsburgisch regierte Städte. Zu diesen frühen slowenischen Freimaurern gehören mehrere Grafen und Freiherren, ein Erzbischof und andere hohe Kleriker, Professoren und theologische Autoren, Buchdrucker und Erfinder, Wissenschaftler, Dichter und Militärangehörige.

Gegen Ende des 18. Jahrhunderts erlebt die Freimaurerei im Habsburgerreich ihren Gipfel und bald darauf durch ein kaiserliches Verbot auch ihren Untergang. Aber ein paar Jahre zuvor entstehen auf dem Gebiet des heutigen Slowenien noch zwei Logen: die Loge ‚Zu den vereinigten Herzen’ in Maribor (damals Marburg in der Untersteiermark) und die Loge ‚Zur Wohltätigkeit und Standhaftigkeit’ in Ljubljana (damals Laibach im Herzogtum Krain). Die deutschen Logennamen signalisieren, dass dies Logen der herrschenden Oberschicht waren.

Die Loge in Maribor wird 1782 gegründet. Sie kommt auf 14 Mitglieder und übersiedelt bereits ein Jahr später in die steirische Landeshauptstadt Graz, also in die damals für Maribor/Marburg zuständige Landeshauptstadt. In dieser gibt es auch heute wieder eine Loge mit der Bezeichnung 'Zu den vereinigten Herzen'.

Die Loge in Ljubljana wird 1792 gegründet. Sie kann gerade einmal drei Jahre arbeiten: bis zum Freimaurerverbot durch Kaisers Franz I. im Jahr 1795. Diese Loge hat 13 Mitglieder, alle aufgenommen in verschiedenen anderen österreichischen, deutschen und ungarischen Logen.

Zweiter Anlauf unter Napoleon

Der siegreiche Napoleon nimmt den europäischen Fürsten nach 1800 einen Teil ihrer Territorien ab: den Habsburgern unter anderem das Gebiet des heutigen Slowenien. 1807 wird es mit den angrenzenden Gebieten zu den französisch verwalteten ‚Illyrischen Provinzen’ zusammengefasst. Napoleons Statthalter sitzt in Ljubljana. Aufschlussreich: Nachdem die Habsburger mehr als ein Jahrhundert später Geschichte waren, errichtet die Stadt Napoleon zu Ehren ein Denkmal, das einzige in diesem Teil Europas.

Für die Freimaurerei ist die Napoleonische Zeit nach der Unterdrückung aus Wien eine gute Zeit. Während Logengründungen im geschrumpften Herrschaftsbereich des Habsburgerkaisers weiter verboten bleiben, entstehen im jetzt französisch geführten Südosten Europas viele Freimaurerlogen. Diese nehmen neben den französischen Beamten und Militärs manchmal auch Einheimische auf. Die französisch-illyrische Loge der ‚Freunde des römischen Königs und Napoleons’ (1811-1813) hinterlässt Mitgliederlisten, auf denen die Namen bekannter Einheimischer vermerkt sind: Anwälte und Richter, Kaufleute und Professoren, Geistliche und Musiker sowie Beamte aus der französischen Verwaltung. Andere Logen akzeptieren nur französische Militärs, etwa die 1808 in Ljubljana gegründete ‚Vollkommene Freundschaft’.

Die napoleonischen ‚Illyrischen Provinzen’ existieren nur wenige Jahre. Nach dem Auszug der französischen Soldaten stellen die Logen ihre Arbeit ein. Nun gilt wieder das Verbot. Jahrzehnte vergehen, die ehemaligen Freimaurer werden älter und sterben.

Erst am Ende des 19. und am Beginn des 20. Jahrhunderts werden einige Slowenen wieder in Logen aufgenommen: entweder im Ausland oder in der ungarischen Reichshälfte der Donaumonarchie, wo die Freimaurerei ab 1867 wieder zugelassen ist, etwa in Kroatien, das zum ungarischen Teil gehört, während das spätere Slowenien zum österreichischen Reichsverband ressortiert.

Dritter Anlauf nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg

Durch die Niederlage Habsburgs zerfällt die Monarchie, und jetzt erst entsteht Slowenien als politisch definiertes Territorium. Es wird ein Teilstaat des ‚Königreichs der Serben, Kroaten und Slowenen’, das spätere Jugoslawien. Logengründungen werden möglich.

In Serbien und in Kroatien ist die Freimaurerei dank eines längeren Vorlaufs schon gut entwickelt. Und so werden einige slowenische Intellektuelle in der kroatischen Hauptstadt Zagreb in die Loge ‚Maksimilijan Vrhovec’ aufgenommen. Und 1940 wird aus dieser Loge heraus mit Zustimmung der ‚Großloge von Jugoslawien’ in Ljubljana eine Loge gegründet, die nach dem slowenischen Dichter Valentin Vodnik benannt wird: und das in einer Zeit, in der Logen überall in Europa aus Angst vor dem Faschismus und den Nazis ihre Arbeit eingestellt haben. Diese einzige slowenische Loge jener Zeit kommt auf 18 Mitglieder, sie arbeitet nur ein Jahr: bis 1941 die Deutschen einmarschieren.

Zwischen den beiden Kriegen arbeiten in verschiedenen Logen im Inland und Ausland etwa 35 Slowenen. Während des Zweiten Weltkrieges haben sich alle außer einem gegen den Faschismus erklärt und sich der Befreiungsfront angeschlossen. Einige slowenische Freimaurer sind von den faschistischen Behörden eingesperrt worden.

Nach der Befreiung 1945 hat auch das kommunistische Regime Freimaurer verhaftet. Die Freimaurerei blieb wie im ganzen kommunistischen Europa verboten.

Vierter Anlauf ab 1990

Mit der Beseitigung des Kommunismus wird die Freimaurerei wieder zugelassen. Zuerst werden drei Slowenen in eine Belgrader Loge aufgenommen. 1991 zerfällt jedoch Jugoslawien in seine Einzelteile, und Slowenien wird ein souveräner Staat. Nun übernimmt die ‚Großloge von Österreich’ den Schutz des masonischen Aufbaus in Slowenien und Kroatien.

In Wien wird 1992 die Deputationsloge ‚Illyria’ gegründet. Sie ist für Slowenien und Kroatien zuständig und arbeitet meistens in Klagenfurt und Graz, gelegentlich auch in Wien, und dann gegen Ende 1992 erstmals in Ljubljana. 1993 wird diese Deputationsloge geteilt. In der slowenischen Deputationsloge sind die Arbeiten oft zweisprachig: slowenisch und deutsch.

Die Zahl der Brüder nimmt stetig zu. Und so können in Ljubljana bald drei vollwertige Logen eingerichtet werden: ‚Dialogus’, ‚Žiga Zois’ = nach Sigmund Zois von Edelstein, einem Laibacher Gelehrten und Mäzen aus dem späten 18. Jahrhundert), und ‚Arcus’ (= lateinisch für Bogen).

Die (reguläre) Großloge von Slowenien

Im Oktober 1999 ist es so weit: Mit Hilfe der 'Großloge von Österreich' werden die drei Logen zur ‚Großloge von Slowenien’ Velika Loža Slovenije, die erste in der Geschichte, zusammengefasst. Sie wird bald von der ‚United Grand Lodge of England’ und vielen anderen Großlogen anerkannt. Ein Jahr später wird dann ein ‚Alter und Angenommener Schottischer Ritus’ gebildet und bald auch ein ‚Royal Arch’.

Stand 2016: Die 'Großloge von Slowenien' besteht jetzt aus fünf Logen mit ungefähr 250 Mitgliedern. Außer den drei erwähnten Logen in der Hauptstadt Ljubljana gibt es seit 2006 eine in Maribor ('Združena Scrca' = 'Zu den vereinigten Herzen': nach dem Vorbild der oben erwähnten ersten Marburger Loge im 18. Jahrhundert); und als bisher letzte eine in der Küstenstadt Koper ('Olivetum' = lateinisch für Olivenhain). Und schließlich eine Forschungsloge Quatuor Coronati.

Die 'Olivetum' aus Koper arbeitet einmal im Jahr über der Grenze im nahen Triest im Tempel der italienischen Freimaurer. Dies sei gar nicht leicht durchzusetzen gewesen, erzählen die slowenischen Brüder, und zwar besonders bei den Italienern, weil offenbar immer noch historische Verletzungen nachwirken: Die slowenische Adriaküste mit Koper (italienisch: Capodistria) war früher teilweise italienisch besiedelt. Nach dem Zusammenbruch der Donaumonarchie 1918 wurde sie ein Teil Italiens. Doch nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg wurden die Grenzen zu Gunsten Tito-Jugoslawiens wieder neu gezogenen. Als Folge emigrierten viele ethnischen Italiener nach Italien, weil sie sich unterdrückt fühlten und nicht in einem kommunistischen Staat leben wollten.

Andere slowenische Großlogen

Großorient von Slowenien

Veliki Orient Slovenije: Ein Freimaurersystem für Männer und Frauen. Die erste Loge dieser Obödienz wurde 1994 von sieben Sloweninnen und Slowenen gegründet: Mitglieder der Karlsruher Loge 'Zur Wahrheit' (Droit Humain) und aufgenommen von dieser in Heidelberg. Sie nannten ihre neue slowenische Loge 'St. Germain' und unterstellten sich der zwei Jahre vorher gegründeten deutschen 'Freimaurergroßloge für Frauen und Männer'. In dieser wurde auch das Andenken an den Grafen Saint-Germain gepflegt: ein Abenteurer und Freimaurer des 18. Jahrhunderts. Die Namensgebung in Slowenien war also eine Hommage an den Grafen.

Nachdem sich die deutsche 'Freimaurergroßloge für Frauen und Männer' 1996 wieder aufgelöst hatte, standen die Slowenen mehrere Jahre ohne Großloge da. Daher afillierten sie 2007 zum österreichischen Universalen Freimaurerorden Hermetica. Aus der 'St. Germain' gingen dann weitere drei slowenische Logen hervor: 'Ex Oriente Lux', 'Sanctum Sanctorum' und 'Hermes'. Und so konnte 2012 unter der Ägide des Großorients von Österreich der 'Großorient von Slowenien' gebildet werden. Er ist Mitglied der AACEE: Association Adogmatique de l´Europe Central et de l´Est.

Aus dem 'Großorient von Slowenien' heraus entstand unter dem Dach des österreichischen interobödientiellen 'Großkollegiums des AASR von Österreich' schließlich auch noch die Perfektionsloge 'Addytum Lucis' (4°-14°).

Reguläre Großloge Sloweniens

Velika Regularna Loža Slovenie: Diese Obödienz entstand als Abspaltung von der oben beschriebenen ‚Großloge von Slowenien’. Trotz ihrer Selbstbezeichnung wird sie von der beispielgebenden 'Vereinigten Großloge von England' (UGLE) und von den anderen regulären Großlogen Europas nicht anerkannt. Es ist unklar, wie viele Mitglieder sie zählt. Sie ist Mitglied der SOGLIA.

Aufbauhilfe aus dem Norden

Der masonische Wiederaufbau Sloweniens erfolgte unter tätiger Mitwirkung österreichischer und deutscher Brüder, was die 'Großloge von Slowenien' betrifft besonders jener aus Kärnten. Gerade das Engagement der Kärntner verdient es, hervorgehoben zu werden. Durch die Geschichte des zwanzigsten Jahrhunderts gibt es zwischen Kärntnern und Slowenen viele wechselseitige Verletzungen, die im kollektiven Gedächtnis fortwirken: zum Glück mit abnehmender Intensität. Und so ist es ein schönes Zeichen gelebter Freimaurerei, dass die Brüder beider Regionen dies einfach vergessen konnten.

History of Freemasonry in Slovenia: Unter diesem Titel brachte das angesehene englische Freimaurermagazin The Square im Frühjahr 2017 eine detaillierte Zusammenfassung der Geschichte der Freimaurerei in Slowenien von den hoffnungsvollen Anfängen im 18. Jahrhundert durch das Auf und Ab im 19. Und 20. Jahrhundert bis zum Neubeginn ins 21. Jahrhundert hinein.

Der Autor Alex Lishanin ist ein Freimaurer, der aus Slowenien stammt und in England lebt. Er ist Mitglied mehrerer Logen und masonischer Forschungseinrichtungen. Sein Manuskript und die folgenden Bilder hat er uns zur Verfügung gestellt. Wir danken Alex Lishanin dafür.

History of Freemasonry in Slovenia

Grand Lodge of Slovenia Memorandum on the history of Freemasonry in Slovenia and its revival notes, Slovenian brethren after being able to use the Temple in Austria for quite some time, decided to organise their own Temple. Upon researching several possibilities, they purchased a house near the Capitol city of Ljubljana, situated 10 minutes drive west-southwest from the capitol. Its reconstruction had completed in the autumn of 1996, where in October of the same year, the Grand Lodge of Austria consecrated the first two completely Slovenian Lodges.

Masonic Heyday in the 18th Century until banned by Emperor Franz

Slovenian Freemasonry has an interesting, intriguing and colourful history. Historian Dr. Matevž Košir, who works at Archives of Republic of Slovenia, wrote a book titled History of Freemasonry in Slovenia. I have taken this article largely from his book.

Soon after establishing Grand Lodge of England, Freemasonry reached parts of Habsburg Monarchy, into which at the time Slovenia had been incorporated. The first person to be accepted into Masonic Lodge from Slovenia was Ljubljana born Johann Karl Philipp Graf (Earl) von Cobenzl in 1741 in Bayreuth (Germany). He was initiated as an apprentice and at the same time passed to fellowcraft into a town lodge. Johann Karel Phillip von Cobenzl later became a bearer of higher Masonic degrees.

In Cobenzl dynasty, there were few Freemasons. Another one was Johann Phillip Graf (Earl) von Cobenzl, born in Ljubljana in 1741, He was a great lover of arts and music. Guests at his mansion near Vienna were many modern artists, likes of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Johann Phillip Cobenzl was a member of a Vienna Crowned Hope lodge (Loge Zur Gekrönten Hoffnung in Wien).

The first Slovenian to occupy Masonic position was noble Josip Pleničič. He was born in Vienna where he studied medicine. Before moving to Prague at age twenty-six, he was already a member of Vienna Three Eagles lodge (Loge Drei Adler). In Prague, he joined a lodge Three Crowned Pillars (Zu den Drei Gekrönten Säulen). In year 1782, he became a member of Czech Provincial Lodge and a year later also a member of a Prague lodge Truth and Harmony (Loge Wahrheit und Einigkeit). In February 1785, Pleničič occupied position of Deputy Grand Master of Czech Provincial Lodge. One of his contemporaries described him, as a man, who was far from medical and political prejudice, equitable, helpful and experienced. His brother Leopold, who occupied various offices in Vienna and in Ljubljana, was also a Freemason.

Slovenian lands in most parts fell under Habsburg monarchy. The first Slovenian Masonic centre within Austrian inner-states was the Adriatic coastal town of Trieste. After Emperor Charles VI of Habsburg (Karl VI., Emperor from 1711 to 1740, father of Maria Theresia) declared Trieste to be a free port, its development and importance grew enormously. At the beginning, Trieste had occasional active lodges that comprised of English and French naval officers during their stay in the port. In 1773, noble Tomas Wezl (Wenzl?), who was a member of military lodge in Magdeburg, was transferred to Trieste garrison. Together with Johann Moritz Hochkoffler, a member of Vienna lodge Tri Eagles, both decided to establish a new lodge. With twelve members in 1773, they established a new lodge under the name Concord (La Concordia)

During the reign of Emperor Joseph II, son of Maria Theresia, freemasonry flourished in Habsburg monarchy. In Vienna alone, there were nine lodges. In 1781 when lodge True Concord was established, Vienna Freemasony of 18th century reached its peak. This lodge was considered elite with literary and scientific ambitions. Members of the lodge were many followers of 18th century Enlightenment movement, writers, poets, composers. There were also members from Slovenian lands, such as Baron Jurij Vega, Vincenc Jurij Struppi, Siegfried Taufferer and Earl Kristian Anton Attems. The Lodge kept lively correspondence with other lodges across Austria and Slovenia - the lodges of Gorizia, Trieste and Maribor. In 1785, Trieste lodge Concord joined with another Trieste lodge Harmony (Loge Harmonie) and formed lodge Harmony and Universal Concord (Loge Harmonie et Concorde Universale). In addition to mentioned lodges in Trieste in 1782, a lodge named United Hearts (Zu den vereinigten Herzen) was established in Maribor, which later moved to Graz. In Gorizia sometime in 1780's, a lodge named Sincerity (Zur Freimüthigkeit) was established and in 1785 counted fifteen members.

Many men from Slovenian lands found their ways to Austrian lodges and even to the lodges in Bohemia, Hungary, Italy, Germany, Netherlands and elsewhere. By the end of century, there were around fifty Freemasons from Slovenian parts. Among the famous ones is Baron Jurij Vega.

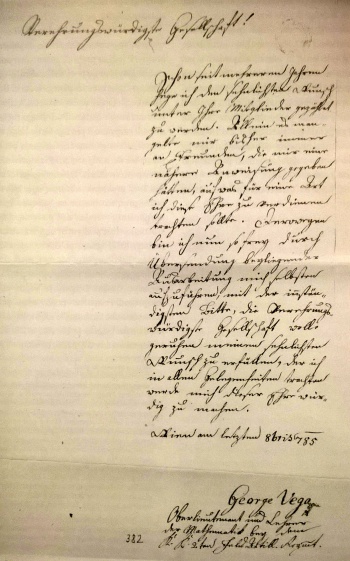

Baron Jurij Vega was born in Zagorica by Dolsko in 1754. He became a Freemason in Vienna in 1785. The meetings in the lodge mixed with his mathematical work, but mostly with his military career as some of his dearest friends in the lodge were also his closest army comrades. Two of his professors, from the study days in Ljubljana, Jožef Maffei and Gabriel Gruber, joined Freemasonry themselves. At age of thirty-one, Vega was accepted into Freemasonry. In his application letter, he expressed burning desire to be accepted into "most esteemed society". Both of his appointed mentors were officers and comrades. Vega fought at Fort Louis, Manheim, Mainz and other battle places. Unterberger gave Vega written support to receive a Knight's Cross of Maria Theresa Order, which he did in 1795. In 1800, he received a hereditary title of a Baron.

The first lodge in city of Ljubljana was consecrated by the initiative of dozen Slovenian Freemasons and Vienna lodge St Joseph. By no coincidence, it happened in mid 80ies of the 18th century, as emperor's Patent (Joseph II. restricted Freemasons in number of lodges and their operation only to capitol cities and regional headquarters.) In 1792 in Ljubljana, thirteen brethren established a new lodge. Each of them had to provide proof of being Freemasons within a regular lodge and with an appropriate Masonic degree. The original yet undated protocol of a meeting was sent to Vienna St Joseph lodge with a request for recognition. With a bill for 81 gulden required to cover the cost of necessary documentation, Vienna brethren sent the request for consecration of new Ljubljana lodge to the Grand Landlodge of Germany in Berlin. With a request, Vienna brethren added their recommendation and expressed strong support for their brethren in Ljubljana. On 2.1.1793 Grand Landlodge of Germany replied to Vienna that constitution for Ljubljana new lodge Charity and Steadfastness (Zur Wohlthätigkeit und Standhaftigkeit), with the rituals for first three degrees had been dispatched. Ljubljana lodge was operative for two years only, until the emperor’s decree of ban on Freemasonry (Franz I./II.). Due to unfavourable circumstances of that time, the activity of the lodge had been modest, but from the correspondence it kept, it was possible to trace that members of the lodge had had great commitment and enthusiasm.

A second but short heyday when Napoleon came to Slovenia

After the French occupation of Slovenian lands and provinces, new lodges sprouted. First of them was a lodge Levant Olive (Olivier du Levant), which started functioning in coastal town of Koper in 1806. Another one, which was a military lodge True Friendship (La partfaite Amitié) was established in Ljubljana in 1809. There were also new lodges in Trieste and Poreč and many other, further into the Croatian lands. Most of these lodges functioned within the frame of French Grand Orient. Most dignitaries in these lodges were French, especially the first lodge officers were French officials and military officers. French soldiers that established the lodge True Friendship had left. Officials, who stayed behind, however started missing the joys of Masonic activity. In June of 1811 they established a new lodge of Friends of Roman King and Napoleon (Les Amis du Roi de Rome et de Napoleon). The lodge counted seventy members. The first head of Ljubljana lodge was Charles Godefroy Redon - General Superintendent of Illyrian provinces. At later date, local Slovenians also occupied the lodge offices.

After 1813: A long prohibition time during the whole 19th Century

In 1813, French departure and restoration of Austrian power in Slovenian lands, caused lodges to seize their activities once again due to the previously issued emperor's ban. Austrian police zealously dedicated their time to finding and prosecuting Freemasons.

Decades later, a division of Habsburg monarchy into Austrian and Hungarian part, resulted each side having its own constitution and legislation. New legislation on Hungarian side allowed societies such us Freemasonry to be active again. Grand Lodge of Hungary (GLH) played important part in restoration and spread of Freemasonry in Slavic south. In 1872 GLH brought Masonic light to the city of Sisak in Croatia by consecrating a lodge Neighbourly Love (Zur Nächstenliebe) and almost two decades later a lodge Blood Brother (Pobratim) in Belgrade, Serbia.

Austrian side also allowed lodges to be active once again but under condition, that government officials had to be present at their meetings. For brethren to have presence of non-Masons at lodge meetings was unacceptable. Consequently, the Austrian side had no lodges until the collapse of the monarchy. This meant, no active lodges on Slovenian lands either. Meanwhile many new lodges grew alongside Austro Hungarian border. In these newly established border lodges Grenzlogen, amongst Austrians, Hungarians and Croats, many Slovenes were found active until the end of WWI.

Under the umbrella of the Grand Lodge of Hungary, relationships between Croatian and Serbian lodges were rapidly strengthening. After the visiting delegations, lodges suggested the continuation of closer ties, coordination of rituals and house order through mutual uniformed principles and more often visits.

1918: A new state now again with freemasonry

After the WWI, with a birth of Kingdom of Serbs Croats and Slovenes, the new Kingdom became a ground for development of south Slavic Masonry. For Slovenians now, the nearest Masonic centre was capitol Zagreb in Croatia. Soon after the creation of a new Slavic Kingdom and The Grand Lodge of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (GLSHS), there was an effort to recover Masonic life and activity in Slovenia once again. In 1929 when Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes changed its name into Kingdom of Yugoslavia, GLSHS also changed its name to Grand Lodge of Yugoslavia (GLY). GLY did not identify itself with politics, but it did support and defend south Slavism. GLY called Freemasons, to within Freemasonry and outside prevent non-patriotic behaviour of individuals and non-respect for national unity.

In the autumn of 1931, GLY approved establishment of Masonic Laurel (Wreath; deutsch: Kränzchen) in Ljubljana and Masonic magazine Šestar (Compasses) noted "strengthening and progress of the Masonic thought, has been observed with a delight". GLY constitution determined as follows - Town that has at least five Freemasons and there is no lodge present, can establish a Masonic laurel, if approved beforehand by the Grand Lodge.

Every member of a Craft Lodge requires an approval from his own Lodge to participate in a Masonic laurel. Masonic laurel is equal to a Masonic Craft Lodge in all aspects, except it does not perform rituals and only accepts members who already are Freemasons in a true and perfect Lodge. Masonic laurel Valentin Vodnik (named after 18th century Carniolan priest, journalist and poet of Slovenian descent), was established on 12.12.1931 in Ljubljana.

The members of Valentin Vodnik laurel met regularly in private apartments and houses or in private room of a restaurant 'New World'. The meeting was opened by WM (Worshipful Master). The word was then given to laurel secretary, who reported on matters arising and correspondence from the Grand Lodge. Among other, members discussed and debated articles from Masonic magazine Šestar. Regular topic was also a cooperation with lodges in Zagreb and Belgrade and a creation of regular lodge in Ljubljana. Regular lodge in Ljubljana was finally consecrated on 21.5.1940 under the same name of 'Valentin Vodnik'. The first and only Worshipful Master of newly consecrated lodge was Dr. Fran Novak. GLY representatives and many guests from Croatian and Serbian lodges attended the consecration but as the political pressures at the time mounted and with the ban on Masonic activities, the lodge was operative only for few months. The attacks on Freemasonry gradually multiplied throughout Yugoslavia. With the information that GLY was receiving, rather than being forcefully abolished, it decided to stop all Masonic activities on its territories and become dormant. During the WWII occupation, Germans started with arrests of known Freemasons. In 1941, Gestapo arrested many Freemasons in Belgrade. Some Slovenian Freemasons, who found themselves on Gestapo lists, decided to move abroad while most of them chose the resistance against the invaders. In the struggle against the occupying forces, the members of Valentin Vodnik lodge decided to join Slovenian Liberation Front.

After little more than two decades it was over again for 40 years

When the WWII ended and Communist Party took control in Yugoslavia, their attitude towards Freemasons was the same as before and during the war. Their stance was that socialism and Freemasonry are not compatible. Events that took place in the life of a Freemason Boris Furlan, are just a small insight into the mindset of post war communist Slovenia.

Boris Furlan born in Trieste in 1894 was educated in private Slovenian schools. He continued his higher education at Sorbonne and Vienna. After the WWI, he worked in Trieste as an assistant in a law firm. During that period, he met many Freemasons. In 1926, he got permission to print magazine 'Law News', which was banned by the Italian fascist regime only two years later. On a tip-off that fascists were planning his arrest, Furlan fled Trieste and moved to Ljubljana, where he opened his own law firm. In 1940, he was among the founding members of Valentin Vodnik lodge. During the WWII, he was on the move once again as Ljubljana occupying Italian fascists still had him on their wanted lists. He fled to Belgrade and from there through Palestine and South Africa he made his way to USA. In 1943, he moved to London where he worked as the Minister of education for Yugoslav government in exile. After the WWII ended, he returned to Slovenia where Socialist Department of National Security started monitoring his movement and activities. Couple of years later, Furlan was arrested and subjected to severe interrogation. That same year, he was one of the fifteen liberal-democratic Slovenian intellectuals accused and court trialled. The court sentenced him to execution by firing squad. After many diplomatic protests, his pardon appeal and probable decisive intervention of English diplomacy, sentence changed to 20 years of imprisonment.

From 1989 on: Slow masonic recovering with Austrian assistance

After the fall of iron curtain in 1989 and establishment of political pluralism, Freemasonry spread across parts of Central and Eastern Europe where it was prohibited for the last fifty years. In 1990, the Grand Lodge of Yugoslavia was renovated and first Slovenians were accepted. These first Slovenians had family relations to pre-war Freemasons of Slovenia. With the break up of Yugoslavia that followed shortly, Slovenian freemasons started forming closer ties with Austrian Freemasons. In Vienna in November of 1991, the conversation between Slovenian and Croatian Freemasons and Grand Master of Grand Lodge of Austria (Großloge von Österreich|GLvÖ) took place, where Grand Master advised that all conditions for GLA (GLvÖ) bringing the Masonic Light into Slovenia and Croatia are coming to fruition. When European community recognised Slovenian sovereignty, GLA realised the idea in supporting restoration of Slovenian and Croatian Freemasonry. In Austrian town of Klagenfurt, under the blue sky in 1992, Provincial Grand inspector and thirteen Austrian brethren consecrated Deputy Lodge Illyria. Illyria was operative in Vienna for both Slovenian and Croatian Freemasons.

New milestone toward Freemasonry in Slovenia was creation of Deputy Lodge Dialogus (Dialog), which took place a year later in the same town, Klagenfurt. At the end of 1995, there were thirty-three Freemasons in Slovenia. By that time, the rituals, constitution, regulations and all necessary Masonic texts were translated into Slovenian language. Deputy lodge Dialogus, was also officially registered in Ljubljana. Slovenian brethren purchased suitable estate, which with their full time commitment, construction work and also a support from Austrian brethren, was refurbished by the end of 1996, where the Masonic light was brought into the Temple. At the same time, two true and perfect lodges were consecrated, Lodge Dialogus and Lodge Žiga Zois. In 1998, the third lodge Arcus was consecrated. The number of brethren that accept Masonic ideas for their own had reached the conditions for establishing a first Grand Lodge of Slovenia.

On 16th October 1999 at noon, Grand Lodge of Austria brought the Masonic Light into the Grand Lodge of Slovenia. With the gavel, presented to the first Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Slovenia, Slovenian Freemasons started their independent Masonic life.

Siehe auch

- Österreich

- Kroatien

- Bosnien und Herzegowina

- Serbien

- Montenegro

- Mazedonien

- Kosovo

- Jugoslawien (1918 bis 1991)

- Albanien

- Regularität

Links

- Großloge von Slowenien: http://www.prostozidarstvo.si/?ln=en&s=2/